In our criminal justice system, a confession is often considered to be the most substantial piece of evidence there is. However, in some cases, when faced with pressing claims, individuals can confess to a crime that they did not commit.

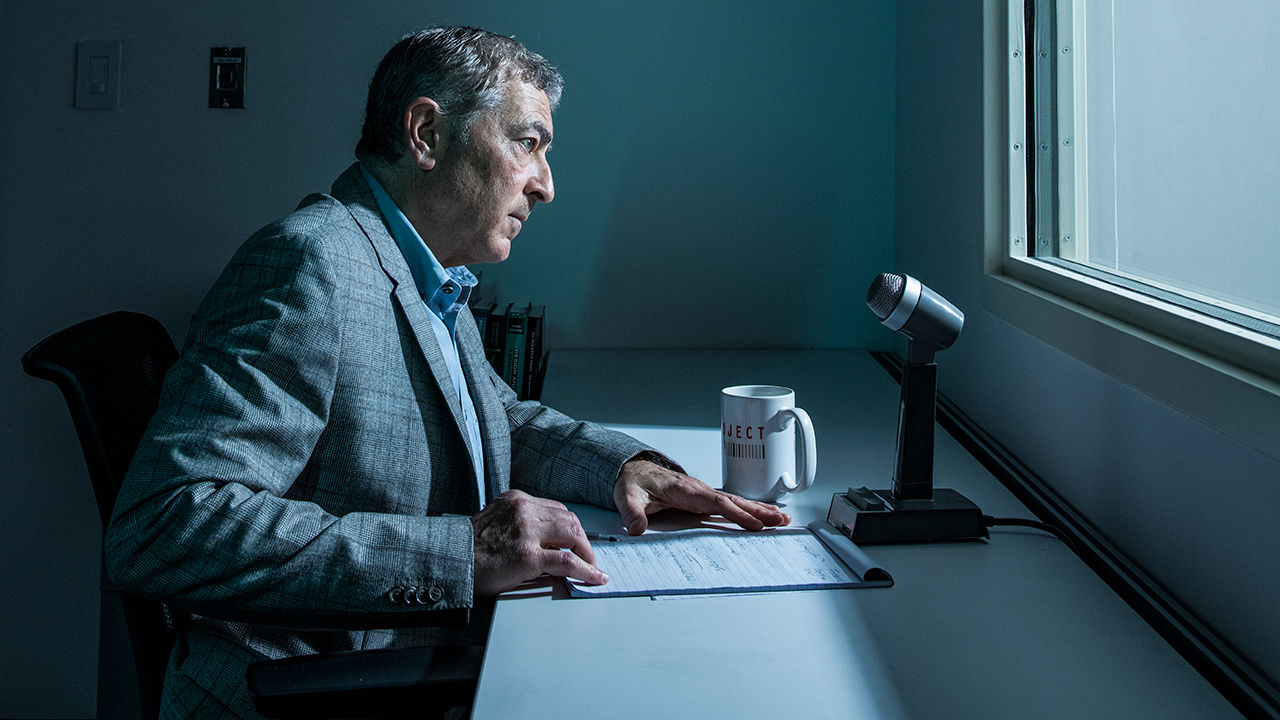

“First of all, people think confessions are perfect. Second of all, given the way they’re taken, they can’t be. Something’s wrong,” said Saul Kassin, a distinguished psychology professor at John Jay College and BC alum, who is well renowned in his field world wide.

Kassin has dedicated his career to studying this phenomenon. After completing his undergraduate studies at Brooklyn College and shadowing a cognitive psychology professor, he gained a deeper understanding of how people responded to difficult situations. This piqued his interest in social psychology and led him to pursue a PhD at the University of Connecticut. “I just found that experience to be electrifying,” Kassin said. “I was interested in the way people perceive themselves and others, and the kinds of influences that people exert over each other. Straight social psychology.”

During his postdoctoral studies at the University of Kansas, Kassin learned of an interrogation manual, which explicitly detailed how to get someone to confess to a crime and the ways in which you can coerce someone.

“Now this was 1978, the concept of a false confession wasn’t really out there,” Kassin said. “I read this manual on interrogation and thought…‘This is Milgram but worse’.” Stanley Milgram’s experiment on obedience found that people will go to great lengths to obey instructions from a perceived authority, even if it involved harming another person.

Kassin pointed out that numerous professionals in law enforcement had read those same manuals and they didn’t think there were any issues. “As a social psychologist trained on the processes of social influence, compliance, conformity, obedience, and persuasion, there was no question in my mind that we had a problem. The problem then was trying to convince anybody else that we had a problem,” said Kassin.

At the time of his studies, there was no hard literature on false confessions. That all changed after the Central Park Five.

He referenced the infamous case that indicted five teenagers on the assault and rape of a woman jogging through the NYC park. “Four of them had confessed on tape. Even I was stumped in my tracks. I thought, ‘Wow, you can get one to confess but four of them? How?’,” said Kassin.

Kassin found that it is not what people confess to but the things that lead them to confessing: interrogation strategies.

Interrogation officers are simply allowed to lie, and about anything. From fingerprints, DNA samples, and even results from a polygraph test. “Police are permitted to do that, present scientific evidence to tell you something about yourself that you didn’t even know. That strikes me as insane, out of the gate,” Kassin said.

He revealed that under certain circumstances you can change someone’s entire emotional state, thus changing their beliefs, perceptions, and memories. “This is not a secret,” said Kassin. “There isn’t a psychologist in the world that would disagree, that when you misinform people about reality, you can change everything.”

Kassin stressed that most people are still greatly misinformed about the way that false confessions happen. “People think that the way that police get innocent people to confess is to browbeat them, yell and threaten them. That’s not how it happens,” Kassin explained. “The way people confess to crimes is through trickery and deception.”

He recalled a case about an 18-year-old named Peter Riley, who although innocent, confessed to killing his own mother. His confession resulted from hours of interrogation and a lie detector test which he eagerly believed would exonerate him. However, police lied and told Riley that he failed the lie detector test.

Initially, Kassin produced the concept of an internalized false confession based on Riley’s case and then found more like them over decades.

He revealed that while minors are more vulnerable to interrogation strategies, anyone can be susceptible to a false confession. In the Central Park Five case, interrogators held the teenagers for hours on end, intimidating and lying to them about the evidence and sequence of events. Eventually, this led the innocent suspects to not only admitting to the crime but describing the ways in which they did it.

“95 percent of proven false confessions contained within them facts about the crime that were absolutely spot-on accurate. Sometimes even exquisitely detailed,” Kassin revealed. “I mean down to the minutiae of the crime scene. Yet, those were not facts that were out in the public domain. So now you ask yourself, well, how did the innocent person know this?”

They got it from the police during the “interrogation mischief,” which the public does not get to see. When a young suspect gets on camera and gives a detailed confession, jurors assume they are the culprit, and therefore guilty.

Looking towards the future, Kassin recognizes that there is still endless work to be done to stop false confessions, acknowledging that solutions aren’t always as simple as knowing your rights. “The solution was supposed to be Miranda rights… that didn’t work out so well,” Kassin said. Miranda, given to us by the courts in 1966, states that suspects have the right to remain silent and have an attorney. “50 plus years later, we now know that 80 to 90 percent of people routinely waive those rights. And we know that innocent people, in particular, waive those rights,” Kassin explained.

Kassin shared that, in almost all of these cases he would ask these individuals why they didn’t just stop talking and ask for a lawyer?

“They look at me like I’ve got two heads on my shoulder and they say, ‘Well, I didn’t need a lawyer. I didn’t do anything wrong.’ Innocent people don’t use their Miranda rights.”

Kassin believes the single most important reform that will eliminate false confessions and prevent the abuse of interrogation strategies is for the state to require a mandate of the full recording of interrogations from start to finish. “Bring them into the room, light gets turned on and so does the camera. Then all interactions between police and suspects should be reported,” said Kassin. “The reason for that is, how can a judge, jury, and a prosecutor determine how voluntary the statement was if they didn’t see the process?,” he questioned.

The notion of recording interrogations has been talked about now for many years. According to Kassin, many police departments continue to skirt the rules, though they exist. Manipulating and omitting footage of the final interrogation tape is common practice. NYS now has a law that requires the recording of interrogations for all major felonies, but even then, there are loopholes to that rule. “I think the most important way the system can react is to require it and to require it without exception. No disclaimers, no disqualifications,” said Kassin.

For Kassin, the ultimate goal is to reform as other countries have in the past. He compared our justice system to that of 1980’s England when there was a wave of false confessions as a result of interrogation strategies. The British courts immediately reacted, revising interrogation rules and made it impossible to lie to suspects about evidence. “New York State legislature has a bill that will eventually come to. It’s actually already in the works. It’s gotten sidetracked by the pandemic but the bill calls for a ban on police lying to suspects about evidence,” said Kassin. “I think that’s an important step, it’s a start.”