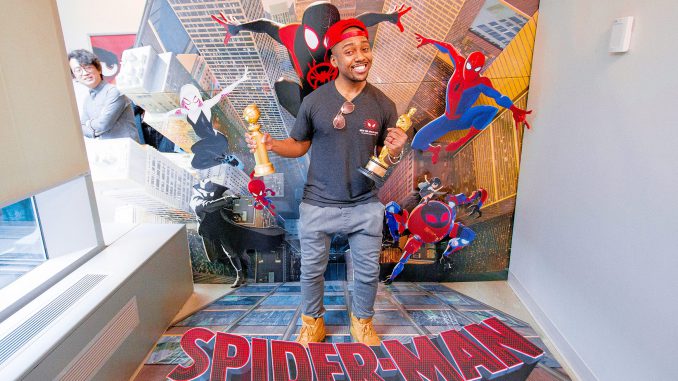

Last year, moviegoers and critics alike were thrilled by the high-flying adventures of Brooklyn teen Miles Morales in the animated hit “Spider-Man: Into the Spiderverse.” But for BC alum Tyquane Wright, an animator on the Oscar-winning team that created the film, “Spiderverse” was a return to the borough that nourished his creative spark.

Wright was born in Brooklyn and raised in the nabe of East New York. It was a rough place and time for Wright, but he didn’t mind it.

“I remember being poor, but then again, those were some of the funnest times in my life, Elementary school was such a blast. I went to P.S. 159, and they had an after-school program where I learned to draw,” Wright reminisced.

When it came time to head off to middle school, Wright went to the now-defunct I.S. 166 George Gershwin, where he studied theater and learned to play tenor sax. He even acted, albeit in a non-speaking part, in the school’s production of “The Wizard of Oz.”

“I was just an elf, but that was the start of me putting myself out there. I was super happy being around other people that were creatives,” Wright said

That may be why he took such a liking to his years at Edward R. Murrow High School, an art school a mile southwest of Brooklyn College. Wright describes Murrow as a creative mecca where students had flexible schedules, and were free to pursue their artistic interests – music, darkroom photography, life drawing classes – with minimal adult supervision. It was a period of great joy for Wright – but alas, it would not last.

“When I left Murrow there was pressure not to do anything artistic,” Wright told Vanguard. “I thought I’d be a doctor or something.” He tried majoring in science at St. Johns, but he wasn’t feeling it – plus, it was a two-hour commute from his new home in Crown Heights. Rather than wake up at 5 AM to take a biology class he didn’t care about, Wright took the spring semester off to work with his uncle, an interior designer. It was then that Tyquane’s father made the suggestion that changed his life.

“By the time summer came around, that’s when my dad said, why don’t you just try a class at Brooklyn College?” Wright recalled. “So I took a life drawing class.” He loved it.

“And from that the professor advised me, just stick around at Brooklyn College and take an art class every semester.”

Wright majored in Computer Science, but his real love was art. He started taking traditional art courses like sculpting and printmaking, as well as painting classes where he’d spend hours working on assignments in Boylan Hall. But by his final year, he began to focus on the burgeoning field of digital art, up to and including learning the 3D animation program Maya. He worked with BC art professor Ronaldo Kiel, for whose class Wright animated a 3D character learning to dance.

“If I had too many complicated lights in my scene, or too many unnecessary data in my scene file, [Kiel] taught me how to save a file to move it along,” Wright remembered. “We managed the scenes efficiently enough that by the time the end of the semester came and I had to prepare my other thesis show, I was able to quickly and efficiently render my final piece.”

Wright was so focused on his work that he says he “took that whole process of graduating for granted until the very day it happened.” That was a big day for him, celebrating his achievement with his whole family and his then-girlfriend (now wife). But then it was back to applying for jobs, and for grad school. He took a job at Cablevision, cutting up trailers for Bollywood films they owned the rights to and then seeing them on TV a week later. And he applied to grad school, ultimately deciding to go to NYU.

“Their orientation was awesome,” Wright remembered. “For the first thirty minutes at NYU, people would come in slowly, and they’d play the credits for Star Wars [Revenge of the Sith]. After the credits, [the dean] said, ‘see these credits playing the whole time? My job is to have you guys as one of these credits.’ I thought, I could be one of the 45 minutes of people.”

Wright had always taken his class assignments seriously – especially at Brooklyn College, where his homework doubled as portfolio fodder – but at NYU, the professors really pushed them to take their work seriously. Early in the semester, he took a class with Carlos El Asmar, who worked at NBC. Dissatisfied with the quality of the student work, he tore into the class – ‘this s–t is easy,’ he said, ‘I do this in forty minutes!’

“He told people to drop out of the program if you couldn’t do better than this in six days,” Wright remembers. “Best speech ever. Once he said that, that’s when I really honed in.”

It was here Wright began to specialize. He took a liking to lighting – managing light sources in a digital environment, and learning how to apply textures and “shaders” to 3D objects so they reflected that light in a realistic way. The final product of these two years of work was a short film called “Dive,” an animation representing his creative process. In the film, a pencil falls to earth, interspersed with drawings Wright made over the past two years. And when the pencil makes impact at the end, there’s an explosion – something Wright included at his professors’ suggestion.

Perhaps the most important suggestion Wright’s professors made was to take care of himself. In addition to his assignments at NYU and his work at Cablevision, Wright spent weekends at 1 Police Plaza, training to become a cop. The police program he was in paid his bills, but it didn’t nurture his soul.

“That’s a chunk of my life that I ignore because I was just there for the money,” Wright said. “I wanted to make money being creative!”

The stress got to him, and he began to doubt his life path – but his advisors told him to not spread himself so thin. “Try to maintain a normal life,” they told him, “and then once you finish the thesis you can say, oh s–t, I maintained a normal life while doing this project.”

So Wright quit his jobs at Cablevision and the NYPD, and focused on himself, both physically (exercise and nutrition) and artistically (seeing films with his classmates). He also took the time to network, meeting fellow artists at the Apple store on Houston Street. In one class, the professor brought in someone Wright had already met at one such event!

It was while networking that Wright had his first big break – a guy he had met at a bar for an event called “PSST! Pass it On” called him at 9 AM on a Saturday and asked if Wright wanted to work on a music video. 24 hours later, Wright was at the guy’s apartment, doing graphics for “American Idol” winner Fantasia Barrino. The job took under a week. Wright thought he was just doing the contact a favor, but soon afterwards he was handed a check from the video’s director for $2,500.

“I cried in the bathroom,” Wright said. “I was like… ‘oh my gosh.’”

Newly armed with the knowledge he could make money doing digital art, Wright started freelancing while he finished up “Dive.” His work caught the eye of a rep from Sony Imageworks, who sent him an e-mail two weeks before graduation. Wright couldn’t believe his eyes; he was certain he was being punked.

“I thought it was spam!” Wright laughed. “So I replied, ‘is this spam, or a joke?’ But it became serious very quick.”

He ended up taking a job with Sony in LA with just his hopes and three outfits worth of clothes. From there, he was offered a job in Albuquerque, testing out “remote workflow” (read: outsourcing work to other studios in real time). The experiment was a success, prompting Sony to open up a second HQ in Vancouver, Canada to take advantage of tax credits. Wright followed suit, and he works in Vancouver to this day.

Wright’s worked on dozens of projects for Sony, some more successful than others. His big success story was “Spider-Verse,” where his Brooklyn roots proved useful when creating a 3D facsimile of the borough.

“There’s one scene where [Spider-Man]’s saving cars from falling off the Brooklyn Bridge. During that scene, my supervisor said, ‘hey Ty, you grew up in New York, does this look like the Brooklyn Bridge?” Wright said. “And I said, ‘yeah, but what about the wood in the center?’”

“Spider-Verse” was a hit both with critics and the public, but some of the films he’s most happy with fell under the radar. He felt especially proud of “Storks” (2016), which he thinks is a “really great movie storywise.”

“It’s kind of a play on Amazon – how Amazon ships things – so they’d rather ship things for profit, rather than ship things that make us more wholesome [babies],” Wright said.

The film was a huge challenge logistically as well. The fictional stork headquarters in the movie is supposed to be three miles long, with a million boxes on screen, requiring exorbitant amounts of data. It’s a far cry from his days at BC, struggling to render relatively simple movements of a single figure in Maya – but advances in software made it possible.

Just as the software he uses has grown, so has Wright – from an excited little kid playing the recorder in East New York to an Oscar-winning animator. He credits his growth to perseverance, and taking advice from his mentors, but also to his self-assurance.

“The film industry is very weird,” Wright said. He says he knows people who worked on the Harry Potter films who made $13 an hour – far less than he did splicing foreground photos into a Fantasia video in grad school. “At some point? Have confidence in yourself.”