I have never seen an angel. Show me an angel and I’ll paint you one,” Gustave Courbet once famously remarked. For the leader of the Realist movement in 19th century France, art was to represent life only as he saw it.

What comes to mind when you hear the term “Realism”? Do you immediately think of painting, drawing, or sculpture? Or is your first thought more literary? Does the word remind you of the works of Henry James and Honoré de Balzac? Is the term wholly assigned to that antiquated project of representation which sought to capture the regular, less-than-pretty lives of regular people? If so, then how would – or could – music fit into this conception of Realism?

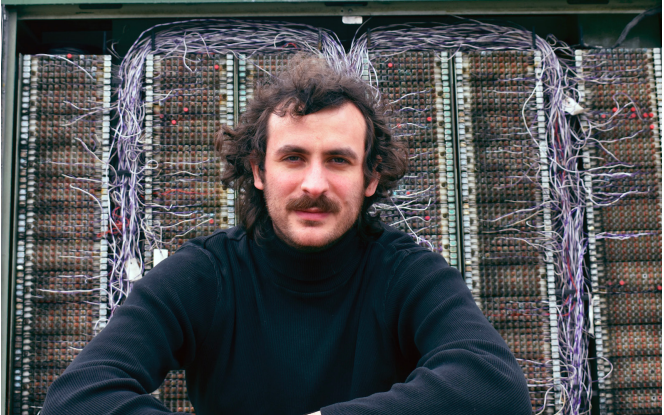

Simon Brown, the easy-going but determined East Williamsburg-based composer, who studied at BC’s Masters Program from 2016 to 2018, has an idea. It’s called, simply, Musical Realism. Brown’s goal with Musical Realism is to render the sounds of the physical world with instruments. The objective is not only to reflect the noises heard every day, but to write fully fleshed-out compositions centered around the representations. Throughout our interview, the wind casted a high pitch whirl through our computer speakers.

Brown was born in Ithaca, New York, raised in the Lower East Side, and went to high school in Western Massachusetts. His first foray into music was through the cello, and his first lesson was at the Third Street Music School. He soon swapped it for the guitar.

“I have a weird relationship with the cello. I really hated it when we moved, because I was getting bullied at school for it,” Brown told me over FaceTime. “When we moved to the country, cello became this thing that was not cool, so I convinced my mom to let me give it up for the guitar.”

Not long after graduating high school in the Berkshires, Brown enrolled in a local community college where the idea for musical representation came to him, “like a lightbulb moment.” Eventually, after completing his Bachelors in composition at Westfield State University, he made his way back to the city and enrolled at Brooklyn College for a graduate degree. As a student here, Brown focused on film composition, and studied under iconic names such as Morton Sobotnick, Tania León (who he cites as the main reason that he applied), Jonathon Zalben, Pat Irwin, and more. Now, he teaches at the Manhattan Youth in Tribeca and Orchestrating Dreams in Inwood.

Since leaving Brooklyn College in 2018, Brown has been getting to know the ins and outs of the industry, and his career is just getting started. In December of 2019, his distinctly Realist piece, “Get Around,” was performed by the string quartet ETHEL at National Sawdust in Williamsburg. The performance featured work by a number of composers such as Sugar Vendil, Sarah Goldfeather, and more.

The kinetic “Get Around” puts one at the center of a rowdy NASCAR track, with hearty cellos and sharp violins bearing the rev of engines and quick whips around asphalt. ETHEL does the piece justice, matching the energy of the composition in their performance as they read from their iPad music stands. The incessant drip of another piece – not performed that night – entitled “liquid liquid,” features a number of string instruments pulling and pushing on varying tones like drops of liquid making shallow, solitary splashes. These compositions take on an uncanny quality because the mimesis is clear – and that’s just where the power lies. While the works strive to be the “real thing,” and to be painstakingly similar reproductions of the original worldly sounds, Brown also exposes the musicality of its origins.

Led by the likes of Courbet, the original Realist movement flipped the reasons for making and consuming art on their head. For the Realists, the goal was not to exalt their subjects or reflect an ideal about life. One could paint farmers, or any physical laborers toiling away at their meaningless jobs; but to represent scenes from famous battles, or from the Bible or Greco-Roman epic poems was not only rejected, but seen as dishonest or untrue. If Courbet were to paint an angel, it would be a lie.

But Brown isn’t interested in these period terms – though his work does complicate and enrich Realism. His focus is on his work, on its potential to push what music can do. And he acknowledges that he isn’t quite the first person to attempt recreating the world’s noises with instrumentation.

“Messiaen was actually really interested in bird songs and would notate them, then reproduce them on the piano or with woodwind instruments. Now, there’s R. Murray Schafer who has done a realistic choral piece with wind,” said Brown from his apartment. “But I don’t want to make sketches. I think of the music as pictures, as real as possible in every sense. A masterful painter can paint someone with one expression but with layers of mood, and that’s what I’m going for.”