on Blackboard

To ring in the 2020 general election, Brooklyn College hosted Black Solidarity Day to reflect on Black people’s contributions in CUNY, America, and beyond. From fighting for more teachers of color to challenging the narrative of Blackness, guest speakers shared their continuous pursuit for change.

Remembering the efforts of leaders before them, like Malcolm X and Toni Morrison, the event recalled the history that empowered Black communities in the first place.

“Black people did not create the need for liberation and power,” said Dr. Jermaine McCalpin, professor at New Jersey City University. “If all lives truly mattered, there would be no need for Black Lives Matter. But because of the existential reality of our oppression, we have to shake off our chains.”

For Carlos E. Russell, the late founder of Black Solidarity Day, recalling Black people’s important socioeconomic and political contributions can remind them of their vote’s importance.

“Growing up, my dad taught me that America is based on two things: democracy – voting – and capitalism. Now to facilitate the change you had to affect one or the other, or both,” said Khari Russell, the founder’s son.

In Russell’s spirit, and in the wake of Black Lives Matter, Dr. McCalpin defined Black solidarity as the unification of Black people, where the common goal is to dismantle the oppressive forces of racism. McCalpin says that to understand this unity, one must understand Blackness’s diversity and the definition of Black power, which is the “declaration of Black humanity and dignity.”

“If Black skin already sets us apart, why not use it to be empowered?” asked McCalpin.

Today’s protests against police brutality, and many social injustices, are a continuation of the struggle that previous activists carried, explained Africana Studies professor Dane Peters. In 1969, 17 BC Black and Puerto Rican students were sent to Rikers Island for 4 days, with bail set at $15,000, after being in a standoff with police. Despite the challenges they faced, these students obtained what they were pushing for – ethnic studies and a step forward in having more peers of color admitted to the then 96% White student body.

“It’s not that things aren’t changing in America. It’s just that this is a constant struggle. This is not one of those things where I’m running in a race, and the race is over, and I won,” said Peters, encouraging students to push for campus policy changes during their time at college. “No, there are other races to be run. There are other battles to be fought.”

For Dr. Clarence G. Ellis, the Department of Education (DOE) Superintendent of Schools in District 17, implementing a “paradigm shift” to the makeup of NYC public schooling staff became his life’s calling. After dropping out of high school in the 10th grade and returning to academia, Ellis realized the significance of having males of color like himself leading a classroom.

“(…)Oftentimes, you’ll see a man with a suit and tie on and has degrees and say, ‘Oh he’s always had it easy.’ Part of this is resiliency – I’m not talking about the cliche of pulling yourself up from the bootstraps – I’m talking about resiliency to odds you never thought you’d overcome,” said Ellis.

Similarly, for Shomari Akil, DOE Restorative Practice Director, the strong relationships between teachers and students can lead younger generations to develop better decision-making skills and to thrive beyond academics. By building a community, students would be encouraged to do better with their studies as well. However, despite the benefits it may have for the child’s well-being, it subsequently burns out many Black male teachers.

“Not only are we required and asked to be the father, the brother, the uncle, but we’re also asked to be the Joe Clark, you know?,” said Akil.

Fondly remembering her days as an undergraduate in the Africana Studies Department at BC, Dr. Trina Lynn Yearwood recalls the significant role her Black professors played in uplifting her. After failing her English class, where her professor called her work “incompetent,” Yearwood decided to venture into her first Africana Studies course called “Black Child In Public School System.”

“The voice that was silenced the year before – I found it in my classes that credited this space for intellectual conversation where I wasn’t the token Black student responding. Where there was validation from my professors and people who really cared about me, who had a real vested interest,” Yearwood said.

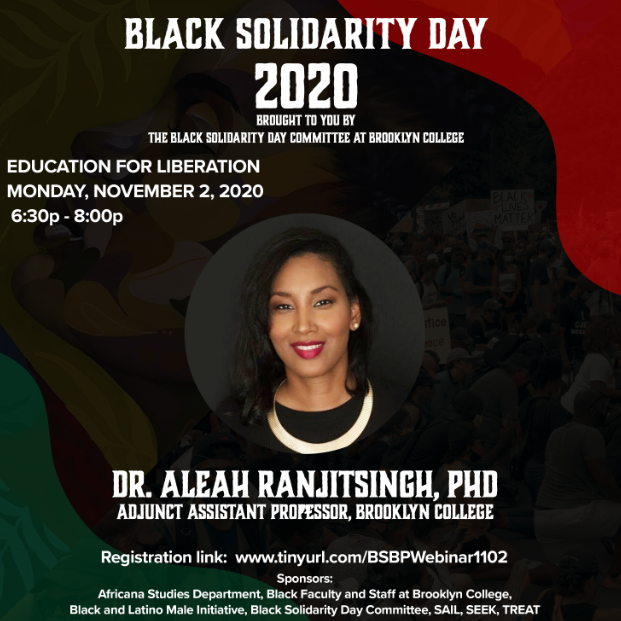

Academically, Africana Studies has enabled Black students to delve into their identity deeper than they initially thought possible. In her course at the Borough of Manhattan Community College, BC professor Dr. Aleah Ranjitsingh teaches about the Black body in American history. She begins her curriculum with a look into pre-colonial kingdoms of West Africa – which is often surprising to many of her students who thought their origins as Black people began with slavery.

“It’s about learning and unlearning, and most importantly, unlearning everything that you’ve been taught about yourself, everything that you’ve internalized about yourself as a Black body, as a Black person. Be it in the US or even the Caribbean space,” said Dr. Aleah Ranjitsingh.

For Robert Jones Jr., author of the upcoming novel The Prophets, minoring in Africana Studies enabled him to call himself a writer and understand different intersectionalities “in the space of Blackness.” Jones credits his development of cultural competence, or the ability to understand and interact with other cultures, to the department.

“I came from a line of people who’ve wrote and read at risk of death, that they could’ve been whipped or murdered for knowing how to read, for knowing how to write,” said Jones. “That it was my inheritance to be able to call myself a Black writer, and by virtue of the fact that I’m writing is always going to be policitized because I’m writing against a narrative about me, about my people about this country.”

With looming cuts in funding for Africana Studies, Jones believes that CUNY is not providing enough financial backing for the department to carry on its role in expanding the understanding of identity among students.

“So, if you’re going to give us this work to do, give us the money to do it,” said Jones.

Through their discussion of Blackness in different areas of society – from academia to civic unrest – panelists emphasized the importance of hearing Black experiences and resiliency. Through this collective reflection, against the backdrop of closing elections, the message remains clear – the fight against social prejudices is a long one, but change must continue to be pursued.