“Futurity, Fantasy, and Technology.”

These are the tenants of afrofuturism, according to Dr. Elizabeth Hamilton, an Assistant Professor of Art History at Fort Valley State University in Georgia, whose research focuses “primarily on race, feminism, afrofuturism, and the impact of visual culture on the lives of black women.”

On Tuesday, Oct. 27, Hamilton joined Dr. Christopher Richards’ ARTD1010 class to give a lecture titled “Narratives of Fugitivity, Black Feminist Futures, and Art History” based on her upcoming book scheduled for release in 2022.

When it comes to the presence of afrofuturism throughout the arts, some might think of Sun Ra, an American jazz composer whose music created a mythology often credited “as a way to liberate black people from oppression in the United States.” This mythology involved Sun Ra imagining himself as from Saturn, instead of his home of Birmingham, Alabama.

“Sun Ra is a pivotal figure in afrofuturist study, but it is here that I want to resist him as the sole architect of afrofuturism,” said Hamilton. “Before there was Mae Jemison or even Sun Ra, there were three women born in the 19th century that traveled among the stars even in their own imaginations.”

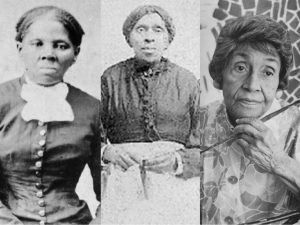

These women were Harriet Tubman, Harriet Powers, and Alma Thomas, who Hamilton claims should all be seen as “progenitors of afrofuturism with just as much as much importance.”

When it comes to Harriet Tubman, Hamilton refers to Celeste-Marie Bernier’s Characters of Blood, where she describes Tubman as “someone who can be considered an artist because of the way that she fashioned her own life.”

The main artwork Hamilton uses to convey this idea is Sanford Biggers’ Codex, which at first glance does not appear to be a narrative of a notable black heroine. Nonetheless, the piece transports those who view it into a celestial environment that does just that.

“Codex is a richly layered narrative of the deeds of Harriet Tubman that relies on the visual language of afrofuturism,” said

(right) were all “progenitors of afrofuturism.”/ Photo Edited by John Schilling

Hamilton. “Biggers defines afrofuturism as a way of recontextualizing and assessing history and imagining the future of the peoples of the African diaspora via science fiction, technology, sound, architecture, individual and culinary arts, and other more nimble and interpretive modes of research and understanding.”

Codex is made up of several hanging quilts painted with constellations that serve as a representation of quilts being used as a sign to fugitives of “safe houses” while escaping via the Underground Railroad. The way they were hung or the patterns depicted on them were deliberate ways of guiding escaping slaves.

The name “Codex” implies that the quilts are to be read as pages in the book of Harriet Tubman.

“Afrofuturism plays heavily in this installation as Biggers identifies Tubman as an astronaut that used the stars to traverse dangerous territory and free those enslaved,” said Hamilton. “Codex is very much about the absence of the body and the possibilities of materiality to convey meaning.”

Similar to Biggers’ Codex, Harriet Powers utilized quilts to convey a neo-slave narrative, a cohesive viewpoint of slavery from the perspective of the enslaved that is supported by collective oral history, acrhival information, and imagination.

Powers was born in Georgia in 1837, and while not much is known about her life, historians have determined that she was deeply religiously and very creative. It is believed that she began quilting at the time of Emancipation when she was 26 years old.

“[Powers] said she desired to preach the gospel in patchwork,” said Hamilton. “She created her own narratives, which carried on oral histories and bible stories, practicing an alternate form of literacy since she was not traditionally literate.”

In 1886, Powers created a Bible Quilt with 11 panels of animals, humans, crosses, flowers, and sunbursts. Among the people are Biblical figures like Adam and Eve, Cain and Abel, and Jesus Christ. Powers’ quilts were considered to be “a hybrid art form” in which she resorted to Chrisitan themes, but the content of her work remained African-inspired.

This is seen more clearly in 1898 with Powers’ Pictorial Quilt made up of 15 panels: ten Biblical scenes and five featuring local history. The two categories are connected, however, by one panel in which Powers depicts the rich people who will not inherit the kingdom of God.

“The celestial phenomenon that filled Powers’ work suggests her succinct consideration of the sweet hereafter and the world beyond Georgia,” said Hamilton. “The Bible stories create a space of the imaginary in her works that deal with fantasy, although…the stories were very real to Powers.”

Powers hoped there was a life better than that of Georgia, and her afrofuturistic desire to flee the South coincided with her desire to be “in the heavenly realm” due to her Christianity. Furthermore, her shift from enslavement to freedom represented “a shift in being” that she worked through within her quilts whilst thinking of elsewhere.

This idea of forward thinking and a progressive point of view is also present in the works of Alma Thomas, the first African American woman to have a show at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1972, whose work focused primarily on the future.

“Thomas was an afrofuturist par excellence,” said Hamilton. “Thomas was an artistic innovator who was not stuck in the past.”

After graduating in 1924 with an art degree, Thomas began teaching but stayed involved within the art community by taking more classes and working with artists of the Washington Color School movement to further hone her craft. Her art career really began, however, after she retired in 1960.

“[Thomas] developed a mode of painting that she called ‘Alma stripes’ that combined a repetitive, effervescent dashes of color with illuminated backgrounds that seemed to shimmer from the contrasts she created,” Hamilton explained.

Between 1968 and 1972, NASA’s Apollo program inspired Thomas to create “space paintings” in which she aimed to explore new perspectives of the Earth from the moon. While some other artists from this time viewed these voyages with great cynicism, Thomas took a much more optimistic approach.

“[Thomas] felt that through art, race could be transcended,” Hamilton continued. “Thomas had a utopian vision in which she could escape racial turmoil through her art.”

Compared to Sun Ra, Hamilton explained that Alma Thomas provides “a feminine perspective” that makes her just as much a progenitor of afrofuturism as he is.

“They are indeed kindred spirits,” Hamilton clarified. “While Thomas does not go as far as Sun Ra in creating a personal mythology, she does identify with the astronauts in her work and strives for alternate futures concerning race in the United States.”

As the lecture came to a close, Hamilton reflected further on these three women as “the architects of afrofuturism” and where she sees afrofuturism going.

“I see it really becoming a way that we think about politics. We have to be able to imagine black futures,” Hamilton said. “Thinking about politics and afrofuturism as a way to imagine better futures and a way to imagine liberation…that is the power of afrofuturism I think.”