By Gabriela Flores

Carrying on the tradition of Black Solidarity Day, Brooklyn College invited professors, students, Brooklynites, and other leaders to speak on Monday, Nov. 1, about the importance of Black people in America. From discussing the power of the Black vote to explaining how to embrace the layers of diversity within the Black community, panelists led their conversations with a constant theme: collective efforts ignite change.

“For me, Black Solidarity Day means really a reaffirmation for us as a community to recognize and commit ourselves to an issue that faces us as a community and how we leverage those things to advance our causes,” said Jesse Kane, the Senior Vice President for Student Success and Enrollment Management at Medgar Evers College.

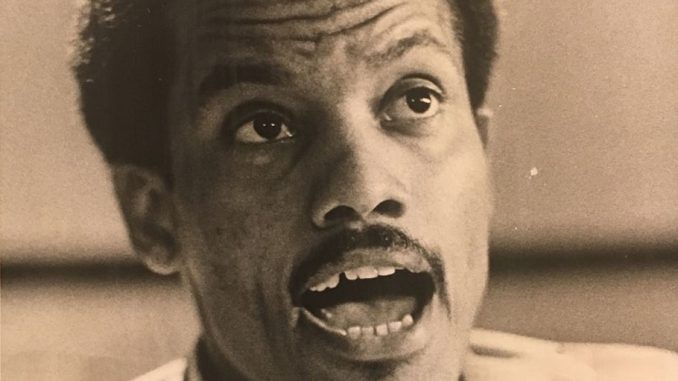

Black Solidarity Day dates back to 1969, when Brooklyn College Emeritus Professor Dr. Carlos E. Russell founded the effort on campus to observe the significant role Black people play in America’s economy and democracy. Dr. Russell, according to his son Khari Russell, was inspired by the play “Day of Absence,” where Black people suddenly disappear from a fictional southern town. The late founder called on the Black community to stay at home a day before general elections, so they and other Americans can imagine how the country without Black people would lead to inevitable tolls in the economy, society, and just about everywhere else. Then, by the following day, Black people were encouraged by Russell to exercise their voting rights.

“And this where Black Solidarity Day comes from – when you take economic power from Black folks and the building power of Black folks, we literally can change this nation,” said his son Khari, later noting that local elections during “the off years” are where ballots shape politics and conditions of communities the most.

For Brooklynite and panelist Jasmine Sykes-Kunk, who works in New York University’s Special Collections, growing up celebrating Black Solidarity Day led her to pass down the day’s purpose to her children. As the observance of Russell’s vision has simmered down throughout the years, Sykes-Kunk found it necessary to continue its teachings and shed light on the omission of Black perspectives in historical narratives.

“I feel as though I always had to have a supplemental curriculum when any subjects are taught to my children in every subject. ‘Well this is what they tell you, but this is where we were left out of these conversations,’” she recalled telling her children, emphasizing how Black Solidarity Day enables Black people to also remember how they have always been and continue being fundamental to American society.

Other panelists later discussed that the labor, spending power, and stake Black people have in the economy could draw more eyes to their advocacy and issues if they were absent for just one day. “Every sector of the economy – Black people are involved. If this labor power is withdrawn, and this spending power is just withdrawn for one day, it would shake up this country. And it would make people pay attention because this money matters […],” said Professor Mojubaolu Okome.

Beyond the hypothetical, however, the unfortunate absence of Black people at the polls is alive and ongoing, according to Cory Provost, a BC alum and the District Leader of Brooklyn’s 58th Assembly District. Within his community, Provost often finds formerly imprisoned New Yorkers who wrongfully thought that their voting rights were stripped away once they served time. He noted that only those convicted of a felony are unable to participate in elections, accounting for 5 million Americans nationwide – with roughly 2 million being made up by Black people. Consequently, he explained, Black voter turnout can be affected locally.

“And that’s what I encounter daily in New York, is that people don’t realize they can still vote, and we see what the absence of that does in our communities like Central Brooklyn or Downtown Brooklyn, for instance, where the most active voters there [are] 80 percent Black women carrying the burden of that community and neighborhood,” Provost said. “Because Black men have been taken away from their communities by the criminal justice system and don’t have that full understanding that they can participate.”

In Russell’s spirit, considering Blackness as an identity that encompasses everyone with descendants from Africa, panelists deep-dived into how the Black community can come together despite their layers of diversity. For Marcus Bright, the District Administrator of 5000 Role Models of Excellence Project, a non-profit based in Florida that aims to eradicate the school to prison pipeline, togetherness stems from removing the “conditional value that we put on people.” Take for instance, he explained, how having a job can deem someone worthy and valuable by those around them. But if they were to become unemployed, their worth to society would plummet. Removing these “superficial characteristics” and seeing eye to eye with someone on a human level could be a way of strengthening the Black community’s togetherness, according to Bright.

“Whether you got $5 or 5 million, your value is not conditional. And I think that’s the basis of unconditional solidarity,” Bright said.

With the backdrop of 2020’s Black Lives Matter protests and similar efforts, panelists shared their thoughts on the presence of allies from different communities. Many agreed that though allies are important, their actions should not be performative or limited to only police brutality.

“For me, I am grateful that there’s broader visibility. Maybe there are people who are shifting and amplifying the work and becoming allies, assistants to move things forward,” said Sykes-Kunk. “I’m just a little frustrated by the performative nature especially when it’s tied to money; all of these companies making statements, but where are they a year later?”

As the panel came to a close, and with elections drawing near, speakers emphasized the importance of exercising one’s right to vote to all participants.

“Civic education is important, and I think everybody that wants to see a transformation of the system we’re in has to engage that,” Professor Okome said, emphasizing that fundamental changes can be done by holding politicians accountable personally and collectively.