By Ian Ezinga

A recent theme in my personal interests and my coursework in my last semester has been the idea of progress. As recently illuminated to me by a professor of mine, there should be an earnest and widespread reorientation amongst concerned citizens about how we all think about the word. Since the Industrial Revolution, the definition of progress has been conflated with ideas of endless growth. Unfortunately, and hence the need for reimagining our thinking about progress, endless growth is a fiction reserved for simulations or fantasy and is not an achievable reality.

Our society has been reevaluating the promises of progress for some time. My professor charted the disillusionment with the idea of limitless growth by using the subject matter found in science fiction. A genre once used to explore exciting new possibilities that lay in the future, is now more commonly digested in the form of dystopian misadventures which paint thoroughly bleak stages for the characters to act upon. Perhaps this is because the stories that the genre generates are just more interesting? But what makes a story interesting besides our capacity to relate to the characters and the world they inhabit? The grand spectacle of the whole thing may be a plausible response. Wouldn’t it be crazy if the world was ruled by a few mega corporations who methodically replaced human labor with artificial intelligence and degraded the natural environment to the point where wealthy people opted to live in outer space instead of the decaying earth?

As out of this world as that may seem, stories of dystopia are not a product of a highly coordinated effort by far-leftist intellectuals to subversively communicate messages about the evils of capitalism. Instead, it is a reflection of the fears that people have, either explicitly or buried deeper in their psyche, that the world isn’t exactly getting better each day and may in fact be getting worse.

To this point, it is interesting to explore the idea of alienation. If all the doom and gloom was even partially based in the present reality, why aren’t there massive demonstrations in the streets and aggressive calls for our elected officials to do something about it? The truth is that there are. But even those among us who are quite active in the pursuit of bringing attention to these issues will always return to our beds at the end of the day and, more often than not, have thoughts about things pertaining to our lives besides the impending climate crisis or the gluttony of the one percent. That is, my friends, called being human. But it is also, in my opinion, a symptom of the alienating effects of being alive in today’s hyper-industrialized world.

One thousand years ago, if you lived along a river and someone upstream decided to dump a bunch of shit in the same water where you drink from, you would immediately know there was a problem and immediately seek a remedy to the problem. Today, most of us have no idea where the water from our taps come from or where the pig that comprised a portion of our breakfast sandwich previously resided. As long as we aren’t homeless or, god forbid, live in a third world country, we are told we ought to be thankful for what we have. Caring about climate change, being concerned about income inequality, or spending your own hard-earned income on a candidate that vows to tackle some of these issues are often made out to good-hearted yet hopeless causes at best, and a complete waste of time at worst.

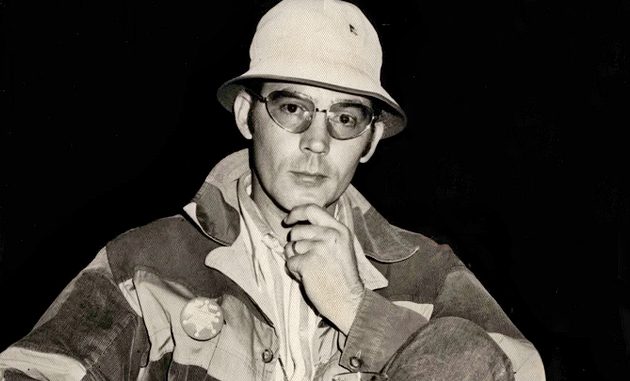

Keep your head down, make your rent, and be sure to file your taxes. These chiding suggestions are coupled with a promise that progress is making everything better; global poverty is on the decline, cures for diseases are being found in record time, and you can have Chipotle delivered to your front door. Considering how alienated we are from the processes that sustain us, it makes sense why it’s so easy to cave in and listen to those who are telling us not to worry. It is as easy for us to become excited at the prospect of a better world as it is for us to lose all hope in the face of the powers that be. Perhaps, we can appreciate the spirit of one of our country’s greatest contributions to the world, Hunter S. Thompson, when he wrote that, “it was the tension between these two poles, a restless idealism on one hand and a sense of impending doom on the other that kept me going.”