It was 20 years ago when Samantha Noël last walked the halls of Brooklyn College as a studio art major with a passion for painting. Since earning her BA in 2001, Noël has gone on to earn her PhD at Duke University and currently works as an Associate Professor of Art History at Wayne State University in Detroit, Michigan, but this almost never came to be.

When Noël first began classes at Brooklyn College, she only had one thing in mind.

“I actually came to Brooklyn College with the intention of getting a graphic design degree,” said Noël. “Then, I took my first course with William T. Williams, and it was such a transformative experience.”

Taking courses with Williams, an American painter and former professor at Brooklyn College, helped Noël realize her passion for painting, but her interests continued to flourish when she began taking an Art History course with Professor Mona Hadler, the current chairperson of Brooklyn College’s Art Department.

“From the first day, I found a new love,” said Noël. “I knew that this was what I wanted to do.”

On Tuesday, Feb. 9, Professor Samantha Noël made a virtual return to Brooklyn College to discuss her new book, Tropical Aesthetics of Black Modernism, as a part of the Ethyle R. Wolfe Institute for the Humanities’s Black Lives: Research & Action Engagement Series.

In the book, Noël’s research aims to investigate how Caribbean and American artists of the early twentieth century used “tropicalist representation” in the visual and performing arts to respond to colonialism. As Noël describes it, this representation was accomplished with paintings that envisioned tropical scenery or bodily expressions that represented the tropics.

Furthermore, Noël argues that these “tropical aesthetics” allowed artists to contribute to “the development of black modernity.”

“My theoretical intervention demonstrates how tropicality holds for a new understanding of the African diasporic experience, a unifying element connecting the black Atlantic that is not generic but creates a linkage between this enclave and the land of origin, Africa,” Noël explained. “This notion of tropicality first disrupts the construction of Africa as the antithesis of Europe and the embodiment of the past, and renders the pan-African world as a purposeful interlocutor of modern life.”

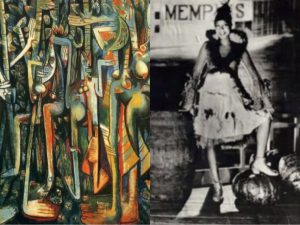

In the lecture, Noël focused on the works of two artists in Wilfredo Lam, a Cuban painter, and Josephine Baker, a French stage performer, and how they utilized the tropics in their work.

When he returned to Cuba from Martinique in 1941, Wilfredo Lam utilized natural terrains in his compositions, and this “self-invention,” according to Noël, was crucial to a new form of artistic expression. Lam was influenced by African-derived worldviews, one of which was the idea that man was not to dominate nature, but to be one with it.

“These ideologies certainly encouraged Lam to re-discover his African American ancestry once he returned to Cuba,” Noël explained. “Through his art, Lam is resignifying the tropical landscape as indicative of modernity but also commemorating the connection that Black Cubans had with the land.”

One of Lam’s most famous works was The Jungle (1943), a painting of four anthropomorphic figures with exaggerated features and surrounded by a tropical collection of sugarcane stalks, tobacco leaves, and palm leaves. Utilizing a rich color palette, what makes this painting significant is its depiction of the figures in a religious procession for Santería, an Afro-Carribean religion, in which they blend in with the surrounding tropical plants.

“Jungle as a construct first became universalized to signify all dance forests of the tropical world,” said Noël. “Using the aesthetic rubric of modernism, Lam’s art makes it possible for the viewer to recognize the ways in which the black masses relate to their environment.”

This theme would also be prominent years prior in “exoticized performances” of the early 20th century that connected Black performers to the tropics through scenic designs, costumes, choreography, and other elements. Josephine Baker was among these performers in La Revue Nègre, a seven act show in Paris that played off of different stereotypes associated with Black people, including what Noël refers to as “sexual ecstasy.”

According to Noël, this stereotype portrayed the tropics as “a hot and torrid zone,” and Baker was at the forefront of this illusion after dancing with Jo Alex, a male performer.

“The sexually-charged performance…featured Baker and Alex in revealing costumes with Baker wearing a feather mini skirt and feathers on her wrists and ankles,” said Noël. “The dance gave emphasis to the hypersexualization prescribed to Black people with a conveyance of tropical Africa in [the] various elements of the production.”

Wilfredo Lam and Josephine Baker each occupy a chapter in Samantha Noël’s new book, which expands further on the development of black modernity with other artists and concepts, but the overall theme remains.

Photo edited by John Schilling

“The creative works of the early twentieth century Black artists…show how this land is revered by its inhabitants who recognize it for its beauty with the intention not to transform it but to accept it,” said Noël. “Ultimately, there is a particular kind of claim to the land that Black people inhabit, which speaks to a desire for [a] home.”