Written By: Nick Wilson

Ted Williams, an almost superhuman hitter, wrote in his 1971 classic “The Science of Hitting” that his first rule of hitting was as follows: “Get a good ball to hit”.

For even the “splendid splinter”, as Williams was known, was not immune to the ailments that plagued his mortal contemporaries in the batter’s box. On the outside corner low and away, the 12 time AL batting champion could only muster a .230 batting average. Low and inside, Williams batted .200.

The fundamental point of Williams’ doctrine was simple: do damage where you can, and survive where you can’t. Once pitchers know where your “happy zones” are, they’ll avoid them. Once they know what pitches you can’t handle, that’s all you’ll see. If you can’t adapt at the big league level, you simply won’t last…unless you’re Gary Sanchez.

When Gary Sanchez first entered the league, scouts saw him as a kid with a raw power, but susceptible to strikeouts. In his first 143 games, the young backstop showed power, smashing 43 home runs and came only three long balls shy of breaking a record set by Rudy York in 1938 (a record which would eventually be broken by a different New York rookie, Pete Alonso). Sanchez was the fastest Catcher in AL history to reach 100 home runs, and within his first three years in the big leagues he found himself holding the single-season record for most Home Runs as a Yankee catcher (a record which he broke again in 2019).

Yet despite this success, the young rookie also had shown some noticeable holes in his game – underlying flaws which ceased to fade even with development and experience.

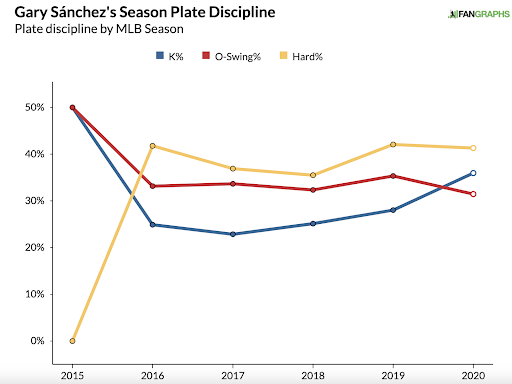

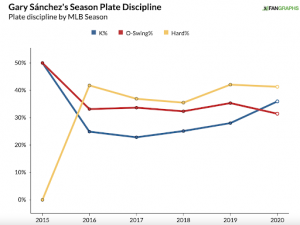

His high whiff rate on fastballs became a troubling reality for a player who had hit 47 percent of his homers on fastballs prior to 2018. He was chasing pitches out of the zone, falling behind in counts, and taking defensive swings to compensate. These defensive swings led to a foul ball percentage on fastballs that went from 14 percent in 2015 to nearly 22 percent in 2016, leading to more strikes and less balls. The number of pitches he chased out of the zone had also remained higher than league average. For all the offensive success Gary was able to achieve, the holes in his game eroded his strengths. It all came to a head in 2018 when the weaknesses of Sanchez’s game led to an abysmal .186 average.

If the ghost of Ted Williams was able to appear and whisper in the ear of Gary Sanchez to provide him hitting instruction, he’d probably remind Gary of his #1 rule: “Get a good ball to hit.”

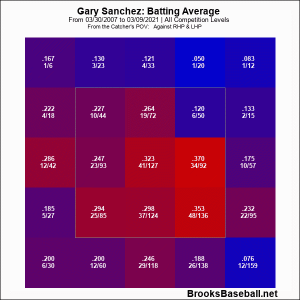

Using Pitch f/x data recorded over Sanchez’s career, we can see a crystal clear picture of where Sanchez likes to hit, and what the results will be. When Gary does get a good ball to hit in one of his “Happy Zones,” watch out.

Not only does Sanchez produce terrific numbers in his hot zones, but what’s not seen in these heat maps is just how hard he hits the ball. On average, Sanchez has hit the ball harder than roughly 80 percent of the league for his career.

Not only does Sanchez produce terrific numbers in his hot zones, but what’s not seen in these heat maps is just how hard he hits the ball. On average, Sanchez has hit the ball harder than roughly 80 percent of the league for his career.

In some ways this works against Sanchez, however. Pitching Sachez in his happy zone is so utterly dangerous, that pitchers thoroughly avoid it. And because Gary chases and whiffs so often, pitchers don’t even have to throw near his happy zone to get him out.

When Sanchez’s offensive value and positional value are decoupled, his value plummets. From 2016-2020, Gary Sanchez’s 115 home runs is first among catchers, but among all other position players, it ranks 32nd (Still not a bad rank, but not irreplaceable).

To provide even further perspective, take a look at Daniel Palka, an adept power hitter from the White Sox organization. In 2019, he hit 27 home runs and batted .240 in just 124 games, but showed poor defensive skills. He found himself playing in Korea the following year.

While Gary Sanchez may never follow the Ted Williams philosophy of hitting, there’s reason to be hopeful that the 28-year-old backstop will return to form. Despite his scuffles, his peripherals have remained shockingly consistent throughout his career. Aside from strikeouts, he isn’t showing any alarming trends in any particular direction, and many believe that much of his struggles offensively have come from Yankees coaches giving him too great a workload. His K% (strikeout rate) is trending in a bad direction, but it’s never deviated more than 4 percent between any two full seasons.

While Sanchez’s strikeout rate (K%) has increased each year since 2017, the chase rate (O-swing %) which has plagued him, has not. He has also continued to crush the ball when he makes contact, as illustrated by the yellow line on the graph that represents the rate in which he hits the ball hard (represented as HH%). If Sanchez is able to lay off pitches out of the zone and get that K% back down to his career average, he should see better pitches to hit. It wouldn’t be the first time a hard-hitting slugger with strikeout issues made significant corrections. Yoan Moncada, Kris Bryant, Trevor Story, and Rafael Devers (to name a few) have successfully done so and seen success.

has not. He has also continued to crush the ball when he makes contact, as illustrated by the yellow line on the graph that represents the rate in which he hits the ball hard (represented as HH%). If Sanchez is able to lay off pitches out of the zone and get that K% back down to his career average, he should see better pitches to hit. It wouldn’t be the first time a hard-hitting slugger with strikeout issues made significant corrections. Yoan Moncada, Kris Bryant, Trevor Story, and Rafael Devers (to name a few) have successfully done so and seen success.

Despite some of the issues that have made Sanchez susceptible to regression, he has seen success even with these struggles. It’s hard to imagine that a player who hits the ball as hard as he does does not find gaps or hits balls over walls. While Sachez’s approach may ultimately stunt his growth at times and limit his ceiling, the floor for Gary Sanchez is more stable than some might think. Don’t be shocked if Sanchez returns in 2021 mashing 30 homers, playing passable defense, and batting an average above .230.