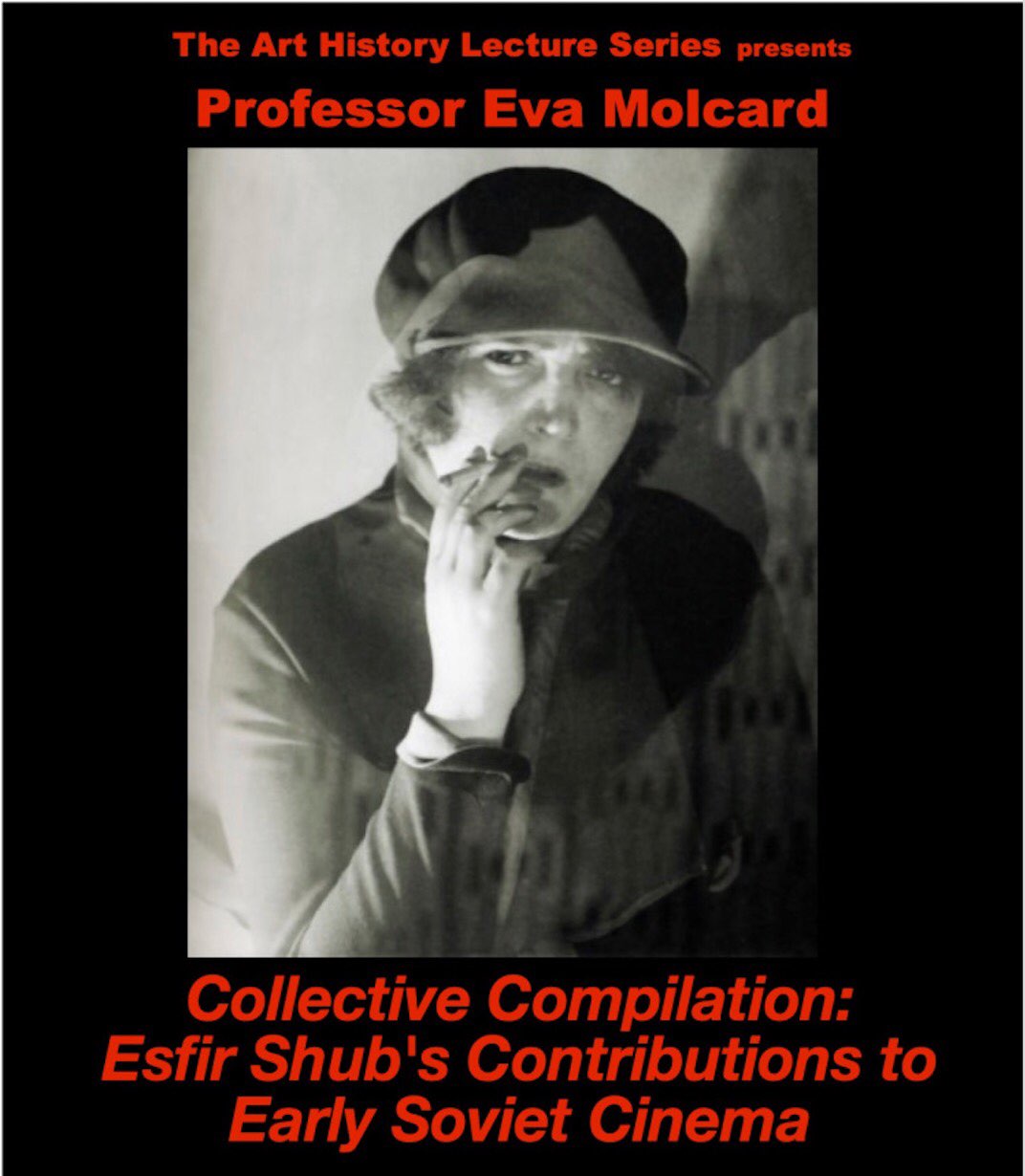

On Mar. 9, Brooklyn College Art History Professor Eva Molcard offered students a lecture that focused on Esfir Shub, a Soviet filmmaker in the early 20th century, and her contributions to “Early Soviet Cinema.”

Despite being credited as “a significant creative force” of the time who invented compilation film in the Soviet Union and enjoying a career that reflected the historical shifts of the time, Shub is often forgotten by scholars who tend to remember the prominent male Soviet filmmakers of the time, such as Dziga Vertov and Sergei Eisenstein.

“Although [Shub] has been referred to as their pupil or assistant, she was in fact their equal contemporary who even taught both of them editing techniques,” said Molcard. “It was Shub’s theoretical and practical work, which clearly functioned as the ideal model of Soviet filmmaking…which reflected the intellectual avant-garde of her time, rather than her male colleagues who have been acclaimed as the apex of the period.”

The lack of scholarly attention paid towards Shub, according to Molcard, is due to a variety of issues. This includes the challenges she faced as a Jewish woman filmmaker during Stalinism and the lack of exposure and access to her films until recently.

In her documentary filmmaking, Shub’s goal was often to capture Soviet history and build a body of work for future generations.

“The aim of Shub’s use of specific documentary material was to preserve and present a foundation of Soviet history, both for contemporary and future audiences to see on film and for contemporary and future filmmakers to use in later cinematic endeavors,” Molcard explained. “Shub was determined to ameliorate the state and condition of the Soviet film archive or rather to establish and produce a working collection of historical documentary film fragments.”

Shub’s film career began at Goskino, a Soviet film company that operated under the government, and it was here that she found her footing. At Goskino, however, Shub’s responsibility was to take existing film footage and manipulate it.

Because the film company was state-owned, films were edited in a way that did not challenge the prevailing Soviet ideology. Shub’s work often celebrated Soviet history, and this became especially evident in her late 1920s film trilogy, “Fall of the Romanov Dynasty,” “The Great Road,” and “The Russia of Nicholas II and Leo Tolstoy.”

For the trilogy, Shub did not film any new material. Instead, she relied on footage recovered from newsreels, state footage of czarist and communist government leaders, and even film from Western Europe and the United States for representation of capitalism.

As a result, one of the biggest debates surrounding documentary film in the Soviet 1920s was the relation of the filmmaker to the piece in terms of objectivity, and Shub was no exception to this. However, Shub’s approach to film was particularly significant.

“It was Shub’s collective centralized approach to film and her archival montage techniques, which provided contemporary critics with a true model of Soviet filmmaking,” said Molcard. “The question of objectivity is of course, a complex one in the Soviet context, given that the majority of leftist or avant-garde filmmakers created films that towed the party line and upheld communist ideals…but Shub’s use of secondhand or found material shot by filmmakers other than herself…provided her with an authorial distance.”

Molcard makes clear, however, that Shub’s editing was deliberate and complete objectivity was virtually impossible.

“It’s clear that Shub did produce visual metaphor to make political point. For example, placing fragments of her champions, laboring workers and peasants in the fields alongside footage of relaxing or even dancing members of the nobility functioned as visual evidence for the need for revolution,” said Molcard. “However, Shub was alone amongst her peers to make the same political point without cutting short, changing or damaging the integrity of the original Soviet documents.”

According to Molcard, Shub’s use of archives and her approach in collecting them was often a source of praise from critics, and this was unlike some of her colleagues at the time. Sergei Eisenstein, for instance, saw himself as an “engineer” of artistic genius and creativity, but Shub’s idea of herself as a filmmaker was drastically different.

“[Shub] consistently envisioned her role as a filmmaker as working as part of a larger collective contributing to the ever-growing Soviet film industry on both a small scale in her immediate team of collaborators and on a grand scale of the industry as a whole building a foundation for audiences and filmmakers of the future,” said Molcard.

Furthermore, Shub often praised other female filmmakers and editors at the time, and there was a mutual respect and understanding amongst them regarding “production in the new Soviet order.” In some cases, Shub would even use her platform to “elevate” the work of other women.

“Their highest quality is their understanding that they are participating in great politically responsible work. Hence they’re disciplined, they’re high standards for themselves and for the purity and accuracy of any task,” Molcard said, quoting Shub. “I do not exaggerate when I say that this team of female assistants is the pride of our studios.”

Ultimately, while Shub and her work may remain in the shadow of her male cohorts, Molcard notes that her legacy lives on in the documentary filmmakers that came after her.

“Her completed feature length films, unmade projects, and rejected film scripts and her private and public written work reveal extraordinary achievement in documentary cinema,” said Molcard. “Her legacy has been limited to the first years of her career and relegated to the status of a mention or afterthought of the period, but her massively innovative work goes beyond the fate of ‘afforded artist,’ and she stands as an inventor and grandmother of documentary film.”