By John Schilling

After a year and a half, in-person performances finally returned to Broadway with “Pass Over,” a play by Antoinette Chinonye Nwandu that focuses on two Black men living in an undisclosed location that is under constant police surveillance.

The play is no doubt a commentary on racial tensions and the police killings of Black Americans, but this production makes clear that the play exists outside of a specific time or place. This is spelled out in the Playbill with the play’s time period listed as “now. right now; but also 1855; but also 13th century BCE,” as well as the place, which reads “a ghetto street; but also a plantation; but also Egypt, a city built by slaves.”

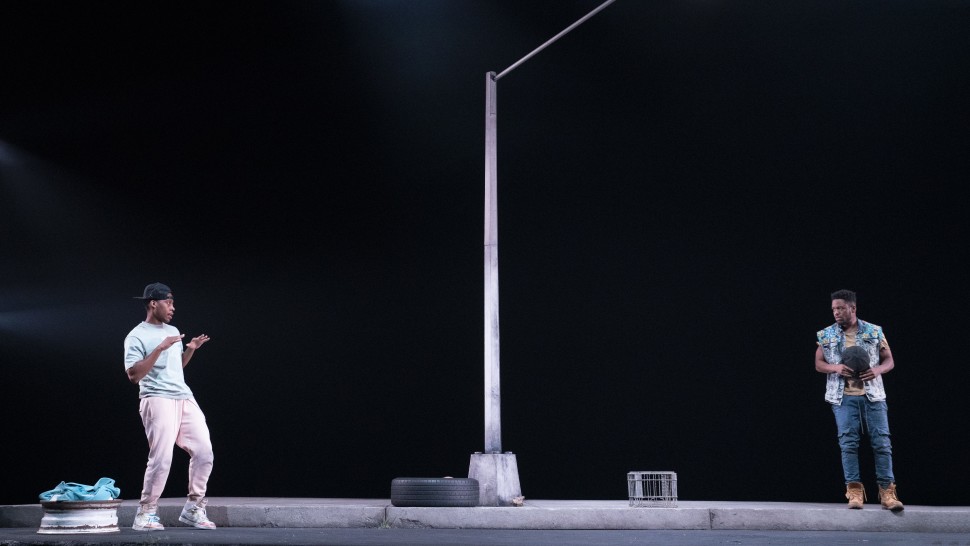

The timelessness of the play is not entirely clear at first as Moses (Jon Michael Hill) and Kitch (Namir Smallwood) communicate with each other using common, everyday street banter and in their interactions with the play’s two white characters Mister and Ossifer (both played by Gabriel Ebert).

As a whole, the three-person cast of Hill, Smallwood, and Ebert is phenomenal, and you can tell right away how vigorous their chemistry is. Through Moses and Kitch, Hill and Smallwood successfully portray two Black men who seek a better life for themselves, or at least one free of the constant fear of the police state they live under. While this is shared between them, the two characters are not carbon copies of each other as Kitch is more open about his fear and the resulting emotions, while Moses remains belligerent to mask his true feelings.

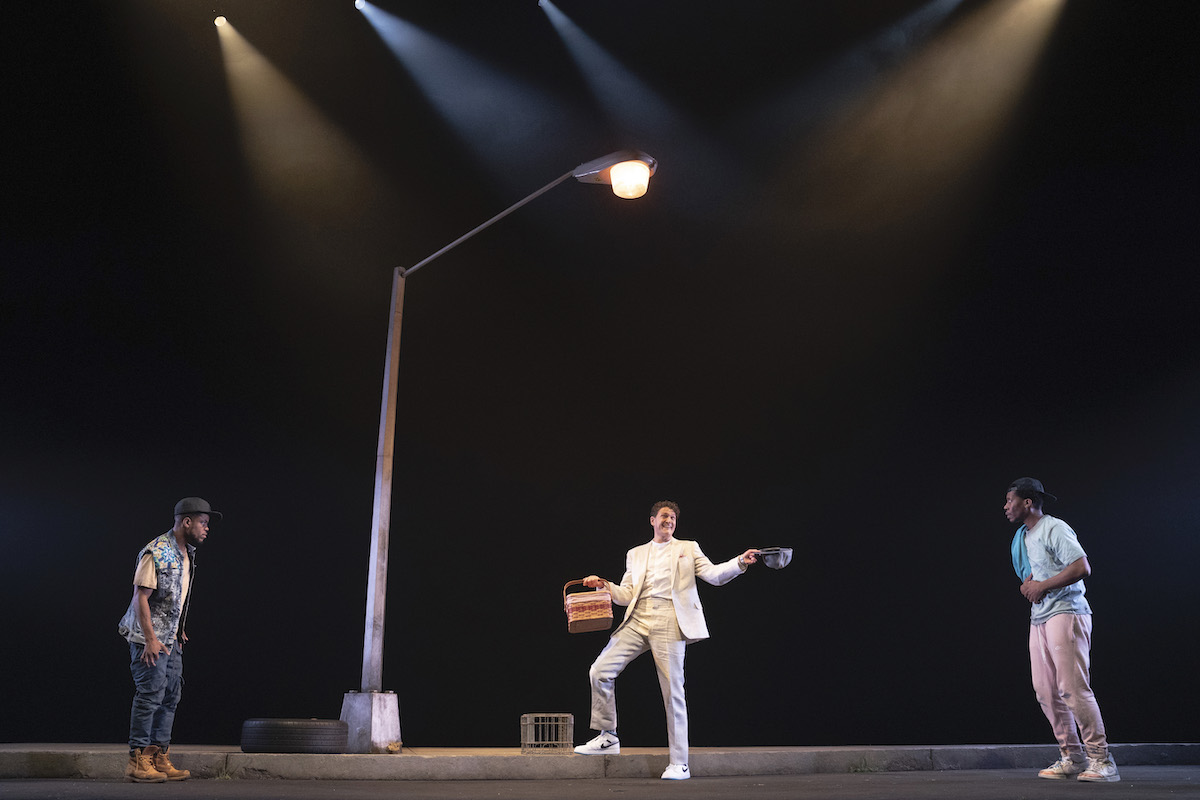

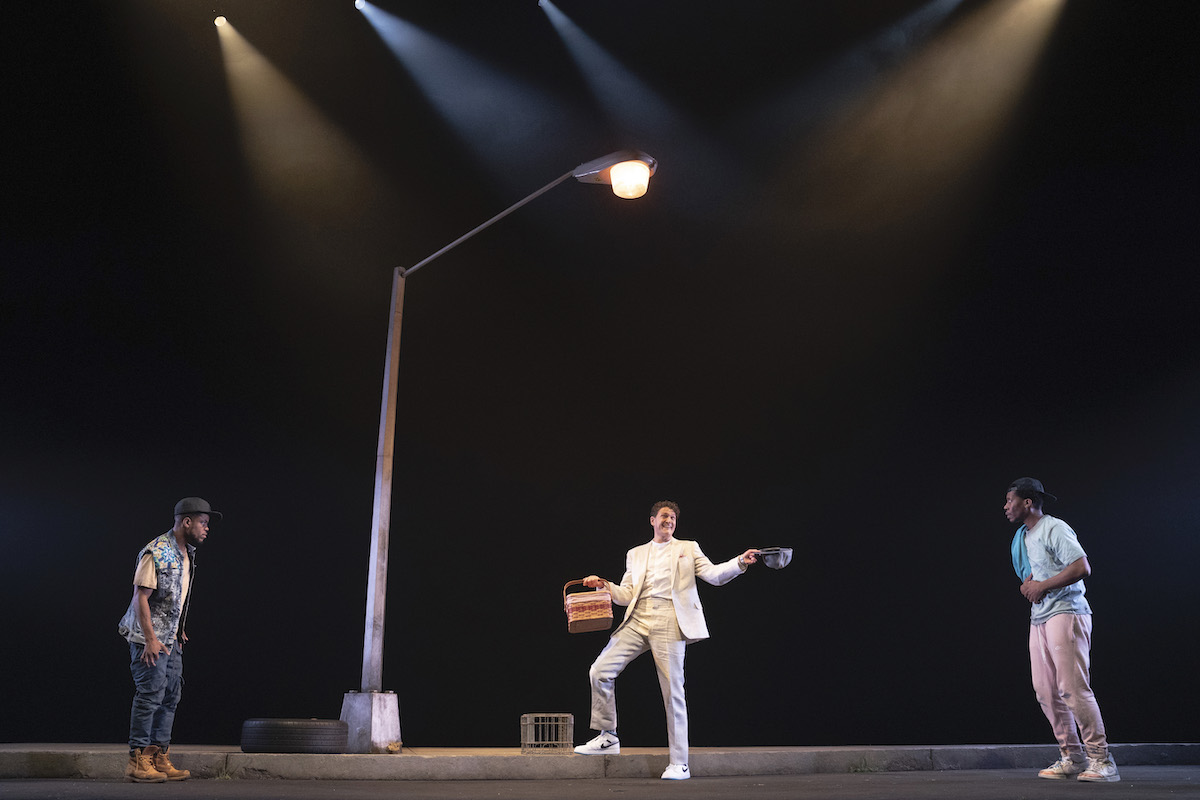

This becomes obvious when Mister passes by the street corner where the two young men reside and offers them food. As the three interact, the play becomes increasingly lighthearted with cracking jokes and even a small musical moment that seems to unite the three. But just when the audience feels as if they can let their guard down and laugh, they are hit with a reality check of racism in America and throughout the world, as well as the role that some white Americans play in enabling it either directly or indirectly.

Gabriel Ebert captures this contrast especially well in his duel portrayals of Mister and Ossifer. Mister is a wealthy gentleman who has never had to pay attention to Black struggles and is alluded to having benefited from them, and the thought of this does not cross his mind until he meets Moses and Kitch. With constant questions of why the two are scared, commentary about their use of the n-word and why he isn’t allowed to say it, and suggesting that they call the police if they feel threatened, Mister’s ignorance becomes very obvious. He seems to be a reflection of white America turning a blind eye to police brutality and/or allowing the struggles of Black Americans to continue without intervention. Indirect complicity, you could say.

On the other hand, Ebert portrays direct complicity as Ossifer, the police officer who storms onto the scene throughout the play to beat Moses and Kitch for disobedience but only when they act as they normally would. At one point in the play, Ossifer is rather pleasant with Moses and Kitch as the two of them begin to speak and act in a performative way. As soon as they snap, however, Ossifer is quick to turn on them, and this speaks to the racist perceptions of Black Americans that have escalated racial tensions in the United States and across the world for centuries.

While the play relies heavily on this symbolism, it is executed in a way that makes it easy for audiences to follow and leaves many things open to interpretation. This is especially true for the play’s ending, which Antoinette Chinonye Nwandu re-wrote for the Broadway production.

In past productions, the play ended abruptly and on a rather sad note. But for Broadway, the new ending takes on a more hopeful approach that ties in directly with the play’s title. The words “pass over” initially refer to Moses and Kitch’s goal of escaping life on the streets and obtaining material wealth. By the play’s end, however, “pass over” takes on a more biblical, allegorical meaning with talks of Moses and Kitch ending their suffering and entering paradise, perhaps heaven or another world free of fear.

This symbolism is the play’s strongest and most creative feature, but it also contributes to its shortcomings. As the play begins to wind down, any sense of reality is sort of thrown out the window, and the play begins to use symbolism in place of reality as opposed to using symbolism as a way of conveying reality. This overreliance on the metaphysical leaves the audience with more questions than answers.

At the same time, many of the play’s aspects are very on-the-nose, relying on highly criticized stereotypes and strong language to make the themes of racial justice, policing, white privilege, white complicity, and white fragility more palpable to the audience. Because of this, the play seems to miss the mark slightly, but it will no doubt start a conversation about the current state of things–a conversation that is long overdue.

These imperfections, however, do not hinder “Pass Over” too much as its strong cast and creative ability to convey heavy material have allowed for Broadway to return on a high note.

“Pass Over” can be seen at the August Wilson Theatre on West 52nd Street through Oct. 10.