By Serin Sarsour

In light of Black History Month, the Black Faculty and Staff at Brooklyn College partnered up with the Flatbush African Burial Ground Coalition to host an event honoring the ancestors of Black people on Feb. 22. An open discussion was held later that week on Feb. 24.

The virtual event hosted panelists who discussed and lectured about the history of slavery and free Black people in Flatbush, and the current struggle that Black people face memorializing the burial site of their ancestors at Church and Bedford Avenue.

“Black history is not just about the past, it’s about how do we make sense of our present. A present that is based on stolen land and stolen lives,” said BC Sociology Professor Lawrence Johnson.

Professor Johnson started the panel off with a moment of silence for all of the enslaved people who lost their lives through struggle and resistance, and the people who passed away during the pandemic.

Johnson emphasized that any real definition of freedom cannot be settled upon without educating everyone on slavery. “The lives of enslaved people and their descendants are the truest testimony of what the United States is and what the United States is not, more specifically what Brooklyn is and what Brooklyn is not,” Johnson said. “The Flatbush African Burial Ground Coalition was formed based on this truth. We cannot respect and value Black lives without honoring and valuing the lives of our ancestors.”

Shantell Jones, one of the members and co-leaders of FABGC, explained that there is evidence from documentaries and anthropological analyses that proves the remains found in the Church and Bedford Avenue area are of African descent. Since New York did not emancipate slaves until 1827, the remains were those of enslaved people. However, the site was never memorialized, and there is no definitive answer on what was done with the remains of the enslaved people or if the remains were treated with care.

The land where the remains were found was once called Lenapehoking, as it was originally occupied by the Canarsie and Munsee Lenape indigenous peoples. These groups were forcibly moved to Ontario, Oklahoma, and Wisconsin due to the Indian Removal Act (The Trail of Tears) that was enacted in 1830, where they still reside to this day. FABGC is hoping to build a strong community with the Lenapehoking people.

The Dutch, who drove the Lenape people out of the area, made what is now known as Flatbush an agricultural hotspot. In 1654, the Reformed Protestant Dutch Church of Flatbush was founded, and still stands today on the corner of Flatbush and Church Avenue, one block away from the Flatbush African Burial Ground. In British Colonial New York, between 1664 and 1731, slave laws stated that people of African descent were not allowed to be buried in the town cemetery, so enslaved people were buried in areas around the church.

Since then, many of the remains of the enslaved people of that time have been excavated, including three teeth and a jaw bone of children younger than 12 years of age.

Although slavery was abolished in 1827, the injustices Black people face did not stop there. With the hopes to urbanize Brooklyn, New York City constructed one of the first public schools, between 1878 and 1894, on top of the burial ground without acknowledging the people who were laid to rest there. FABGC’s mission is to ensure that the memory of Black ancestors and slaves is not lost with the many buildings that have been built on top of the burial ground since then.

More recently, a large population of Caribbean American immigrants made a home in Flatbush during the mid-1980s. This population would soon go on to have plans to build a cultural institution in the neighborhood in the mid-90s with the help of The Caribbean American Chamber of Commerce and Industry (CACCI), as explained by another member and co-leader of FABGC named Samantha Bernardine. However, the funding for that institution was mysteriously pulled and redistributed elsewhere, operating as another example of injustice Black members of the Flatbush community faced.

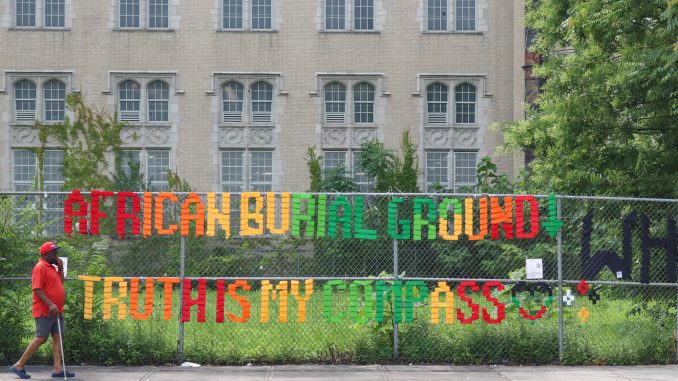

FABGC has been working to make these injustices heard and seen, and to correctly honor Black ancestors through the burial ground.

“We’ve engaged nonstop for over six months with 400 plus community residents, activists, artists, educators, organizations, and we’ve met with local officials about how to protect the property [of the burial ground] and to actually re-envision how it could be used,” said Allyson Martinez, another member and co-leader of FABGC. “Urban design and planning could be used to better inform the community and to work to protect the burial ground.”

FABGC has also led community engagement initiatives, such as collective art-making and beautification, to bring the Flatbush community together.

“My biggest fear is that as the Flatbush community is starting to be gentrified and changed, that history of the Caribbean and African descent, as well as the Lenape people, will continue to be forgotten,” said Bernardine. “Brooklyn College, we need your help. We need access to resources in order for us [FABGC] to be successful, for us as a community to be successful.”