By John Schilling

The day was Tuesday, Aug. 17, 1948. Philadelphia Phillies pitcher Sam Nahem headed for the mound in the top of the sixth inning, preparing to face Brooklyn Dodgers rookie catcher and eventual Hall of Famer Roy Campanella.

The Phillies, who trailed the Dodgers 5-0, were right at home in Shibe Park, located in the heart of Philadelphia, but to say that Nahem was at home would not be accurate.

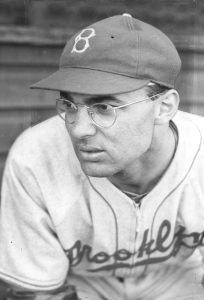

Nahem was no stranger to the Brooklyn Dodgers or Brooklyn as a whole, as he had begun his career with the Dodgers in 1938 at 22 years old, graduated from Brooklyn College in 1935, and grew up on Ocean Parkway for most of his childhood as one of eight children to Syrian Jewish immigrants.

As a Brooklyn Dodger 10 years prior, Nahem was not a teammate of Campanella, who at the time, still played in the Negro Leagues with baseball having yet to be integrated. When Jackie Robinson broke Major League Baseball’s color barrier in 1947, Campanella would join the Dodgers the following year, but the racist attitudes of the time were far from over and Black baseball players continued to face abuse both on and off the field.

Despite Nahem’s Brooklyn roots and familiarity with the Dodgers, he was very much a stranger to Campanella, a fact that would prove itself within the at-bat.

That season alone, Campanella had been thrown at a lot by racist competitors who resented him for the color of his skin, and during this at-bat, there was one pitch that Nahem lost control of and came close to plunking Campanella in the head, a moment that would stick with Nahem years after.

“A ball escaped me, which was not unusual, and went toward his head,” Nahem recalled in “The Whiz Kids and the 1950 Pennant,” a 1996 book by C. Paul Rogers and Robin Roberts. “He got up and gave me such a glare. I felt so badly about it I felt like yelling to him, ‘Roy, please, I really didn’t mean it. I belong to the NAACP.’”

What Campanella didn’t realize then and what many today still don’t realize is that before Jackie Robinson integrated baseball, Sam Nahem was one of baseball’s fiercest advocates for the sport’s integration and often tried to convince his teammates of this position in New York and the places he would go thereafter.

Nahem’s outspoken nature, however, was not always a part of who he was or how he conducted himself. His impetus to speak up against injustice was born from a passion for political activism that manifested itself during his years at Brooklyn College.

While Nahem was right-handed, his politics were left-leaning, and this led to his involvement with a Communist Party campus group during the Great Depression. Before his Brooklyn College days, however, Nahem was not as outspoken.

“I think Sam was very proud that he [had] gone to Brooklyn College,” Ivan Nahem, his son, told The Vanguard. “As I knew him, he was very much an extrovert, but he would say that he was actually very shy before he became a star athlete, and he made this transition while at Brooklyn College.”

Despite not making his high school baseball team, Nahem was a Kingsman through and through at Brooklyn College, where he pitched for the school’s baseball team and even played quarterback and fullback for the football team.

Between his on-field athleticism and off-field activism, Nahem seemed to have left very little time for his studies, something that his son, Ivan, learned along with Occidental College Professor Peter Dreier when the two researched him for a story in late 2020.

“Peter and I were surprised to learn that his academic record, which I requested from the school, was actually subpar,” Ivan Nahem told The Vanguard. “He was a sophisticated thinker and surely would have done well if he had applied himself. It’s possible that his passion for sports interfered with this.”

What Nahem may have lacked at Brooklyn College, he made up for in the years that followed. After graduating, Nahem signed with the Brooklyn Dodgers and spent three years in the minor leagues. Within that time, according to the Jewish Baseball Museum, Nahem was “discovered” by Dodgers Manager and eventual Hall of Famer Casey Stengel, who first noticed him pitching batting practice at Ebbets Field in 1935 and could not hit off of him when got into the cage to try.

As previously mentioned, Nahem would finally reach the Major League level in 1938, and it was here that he would begin to speak on baseball’s integration.

“In New York if you’re young and Jewish you’re political,” Nahem told The Jewish News of Northern California: J. in 2003. “And I did my political work there. I would take one guy aside if I thought he was amiable in that respect and talk to him, man to man, about the subject. I felt that was the way I could be most effective.”

Oddly enough, Nahem, by his own admission, found himself in these positions throughout his career as most of the places he played were made up of people vehemently opposed to the integration of baseball and Black baseball players in general.

After only one game with the Dodgers in 1938 in which he pitched all nine innings, surrendered three runs, and still recorded the win, Nahem was traded to the St. Louis Cardinals in 1940 and found himself back in the big leagues in 1941, a career season he would finish with a 5-2 record, a 2.98 ERA, 31 strikeouts, and just under 82 innings pitched.

One year later, Nahem switched teams again with the Philadelphia Phillies purchasing his contract from St. Louis, and it was here especially that Nahem found himself at odds with some of his teammates, which prompted him to speak about the issue of integration individually instead of openly.

“One of the southerners was fulminating in the clubhouse in a racist way and I made some halfway innocuous remark defending blacks coming in to baseball,” Nahem revealed in “The Whiz Kids and the 1950 Pennant.” “Boy, he went into a real tantrum and really came down on me. So I decided I would not confront anyone openly. Your prestige on a ballclub depends on your won-loss record and your earned run average. I didn’t have that to back me up. I only had logic and decency and humanity. So after that I would just speak to some of the guys privately about racism in a mild way.”

While Nahem called for integration early on and challenged those who complained when it finally happened, his biggest accomplishment came on the field, but not a Major League Baseball field.

After pitching 35 games with the Phillies in 1942, Nahem enlisted in the U.S. Army that November during World War II, hoping to aid in the fight against Nazism in Europe. During his first two years of service, Nahem was stationed at Fort Totten in New York, where he continued to play baseball, a program the military would expand after Germany’s surrender in May 1945.

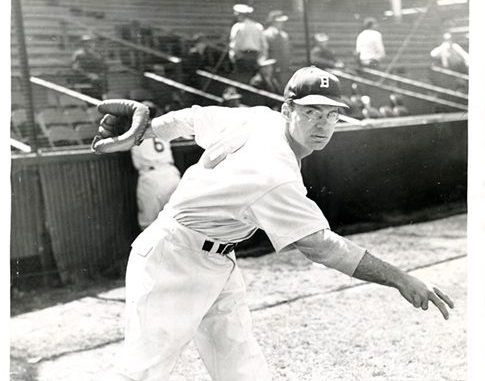

When this happened, Nahem, who had been sent overseas to a base in Reims, France the year prior, ran two baseball leagues while also managing and playing for the Overseas Invasion Service (OISE) All-Stars, a team “which represented the army in charge of communication and logistics,” according to Forward.com.

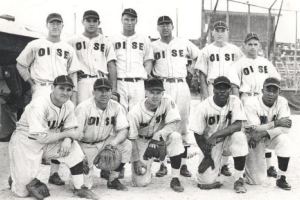

Consistent with his beliefs about MLB, Nahem wanted African American baseball players on his team, something that would go against military tradition and had not happened yet in MLB. While African Americans were permitted to serve, segregation and racism were still very common, and like MLB, Black soldiers were limited to all-Black teams.

Much like Dodgers General Manager Branch Rickey would do with Jackie Robinson, Nahem went against tradition and recruited two African American players for OISE in 1945: outfielder Willard Brown of the Kansas City Monarchs and pitcher Leon Day of the Newark Eagles.

This decision, while historic, proved to be effective as well. OISE finished with a 17-1 record and went on to win the GI World Series against Germany’s Red Circlers. One month after OISE’s victory, Branch Rickey signed Jackie Robinson to a contract, but Robinson would not break MLB’s color barrier until two years later when the Dodgers finally called him up.

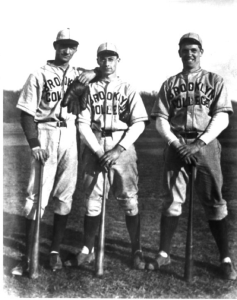

Nahem would return to the big leagues a year after that in 1948 as a member of the Philadelphia Phillies once again, but his 3-3 record and 7.02 ERA across 28 games and 59 innings pitched indicated that his best days were behind him. He would never see MLB playing time again but kept with the sport for the San Juan team in the Puerto Rican League toward the end of the 1948 season and for the Brooklyn Bushwicks, an independent team, during 1949.

In the years after, Nahem’s leftist ideology made him an easy target during the Red Scare. Nahem, who had pursued work as a law clerk, salesman, and longshoreman, lost many jobs during this time as FBI agents alleged he was a “Communist” and informed his employers of their suspicions.

This prompted Nahem to move to San Francisco in 1955 with his wife Elsie and their three children. In California, Nahem worked at the Chevron fertilizer plant and left the Communist Party but remained civically engaged, often taking his children to “civil rights and anti-war demonstrations,” according to Forward.com.

Nahem never returned to Brooklyn or New York City before passing away in 2004 at 88 years old, but the opportunity did present itself in the 1980s at Brooklyn College no less.

“I […] recall that sometime maybe in the late 80s he was offered a coaching job at Brooklyn College. I think it was for the football team,” Ivan Nahem told The Vanguard. “I think he considered it, but he loved living in his home in Berkeley, and didn’t want to return to New York City.”

Still, while Nahem left Brooklyn, Brooklyn never left him, and that voice he gained during his years at Brooklyn College inspired him to do great things.

So on April 15, when Passover begins and MLB coincidentally honors Jackie Robinson for breaking MLB’s color barrier in 1947, let us also remember Sam Nahem, a Brooklyn-based Jewish man who called for and began baseball’s integration in the military years prior.