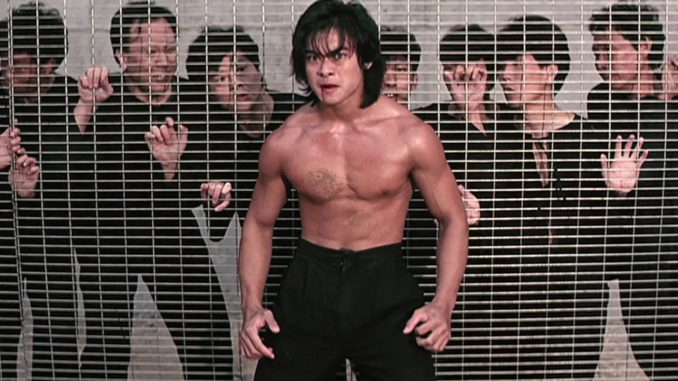

Shea Stevenson

“Riki-Oh: Story of Riki,” a 1991 Hong Kong film adaption of a Japanese manga of the same name, boldly asks in an opening title crawl for the audience to imagine a capitalist hellscape in which prisons have become privatized. From an American perspective, this is almost a punchline in and of itself; state-level private prisons have been opening since 1986 and can be dated in the U.S.A. as far back as 1852. But this movie cares little about the history and politics of incarceration – it seems to think two things about private prisons:

1) Action scenes in prisons are badass.

2) People who run private prisons are evil (and may be the subject of righteous violence).

Because when it comes down to it, “Riki-Oh: The Story of Riki” is only interested in one thing: righteous violence, or violence towards someone deemed deserving of it thus removed from the ugly connotations of common brutality. It believes in righteous violence with such pure-hearted devotion that it almost amounts to thematic depth in a sagely blank clarity. Let me backtrack with some context.

My first encounter with “Riki-Oh” was on YouTube and surely too young. It was one of the hundreds of movies that swirled in the miasmic canon of the late 1990s to early 2000s underground shock-cinema that became the backbone of many early internet subcultures, continuing the legacy of the VHS-ripping scene. The movies that were passed around remained largely the same but now had a mythic quality to them; because the movies were so inaccessible, but their names were well known, reputations tended towards exaggerating what people had already heard and continued repeating.

I heard that “Riki-Oh” was the most excessively violent movie of all time. I still don’t know if that’s true – but if there was ever a test of those things, I’d be rooting for it. In mentions, it seemed to me to come with a “only watch if insane” caveat. Certainly a part of this was the then in vogue notion that Japanese media was particularly strange and perverted (a take that still haunts us) even though, as stated previously, the movie is from Hong Kong.

I come to you to say that if you can stand the sight of blood, you should watch “Riki-Oh” even if you’re not insane. Because the virtues of “Riki-Oh” are the virtues of all action cinema, and the vices of “Riki-Oh” are only in spurning disguises we’ve become too used to.

Action cinema has one unifying ingredient: righteous violence. Without violence, there is no action. If the violence is not righteous, we call it horror. But filmmakers, especially in Hollywood, seem embarrassed of this. They want us to indulge in righteous violence, otherwise why make an action movie? But they understand that to endorse it in narrative is uncouth to a modern audience. We’re to understand that revenge is bad, that pacifism is good, and that we don’t like murderers. So filmmakers introduce moral ambiguity, remove the blood, and punish characters for over-indulgence in violence.

I’m not about to tell you those things are bad. In fact, I happen to agree with most of it. The problem lies not in its morality, but in its philosophical clarity. Again: why make an action movie if you’re not interested in righteous violence? If you’re going to commit, commit!

“Riki-Oh: The Story of Riki” is not the best action movie, but it has a magnetic clarity of purpose. Instead of half-hearted mollifications that suggest “we’re not hurting anyone that bad, it’s ok,” it focuses all of its power into invoking ultimate righteousness and unimaginable violence – becoming the final form of modern action cinema.

The titular Riki is as pure hearted as they come, and his adversaries are literally the overseers of a for-profit people-dungeon. When Riki punches something, his fist either goes through it or detonates it.

And when he does evict a guard’s brain from their skull, he looks back into the past at all action cinema and asks, “Am I not your son? Is this not what you feigned but never had the courage to grasp?.” Do what you will, we come to the action movie to see heads roll. And I think that’s cool.

Its complete commitment to its own bit makes “Riki-Oh” worth your time in 2022. There has never been a movie like it, and no imitators reach its heights. For those among you attuned to internet scavenging, “Riki-Oh” is available online if you know how to seek it. Without an in-print physical release in America at time of publishing, it goes against its legacy for me to recommend you rent it for streaming. Find it or don’t. As Riki teaches us, the only sin is lack of commitment.