Shea Stevenson

When describing ancient Mesoamerican ball games, a teacher of mine once said that they were “intensely religious, ritualistic games” and that “the players wore garments resembling animals, perhaps to embody their characteristics.” This moment has stuck with me because, beyond the exoticized language, that’s American sports.

I don’t mean in the snide “people like their teams so much it’s a religion” way, but that by any definition of the word “ritual,” all American sports are steeped in pseudo-secular ritualism. Sacred realgia (jerseys, facepaint), repetitious mass chanting, and in one way or another, often literally praying.

Prayer, secular and otherwise, is omnipresent in American sports. Not to mention we still wear animals on our sports uniforms. Do the Brooklyn Bulldogs wear their jerseys to embody the spirit of a bulldog? Perhaps not.

And if future archaeologists dredge New York from the ocean floor, how might they interpret Yankee Stadium? How about the thousands of gyms, some dedicated to a single sport? How about these grass diamond baseball fields carved into otherwise towering grayness? How about the concrete piers by the promenade, massive slabs laid overtop of the most ancient blood vessel of the city, dedicated entirely to basketball courts?

We as archeologists would assume that these structures must have religious significance. So much space and tax dollars are put into the construction and upkeep of these stadiums that there’s no way people would just… do this, right? But archaeologists of the future will be smarter than that. They will look upon our sprawling sports fields, and our million-dollar courts, and they will say, “these people liked games.” Even if we think we don’t.

In American culture, games don’t matter. If something is “just a game to you,” you don’t care about it. Yet if there’s one thing that humans resoundingly do care about, it’s games. For as long as we’ve left traces of existence, we’ve played games, and to think that cavemen weren’t playing things around as complex as we do now is unimaginative. We’re just cavemen in office buildings. Games, like all forms of art, are apparently a human necessity.

Perhaps it’s the segmentation that Americans perform between “sport” and “game.” Though a game is meaningless, a sport is important. Many people dedicate their entire lives to sports and never play them professionally. It’s a multi-billion dollar industry. It’s an American institution! That’s the crux of the repulsion many sports fans feel when that distinction is challenged: a sport can be serious, but a game can’t.

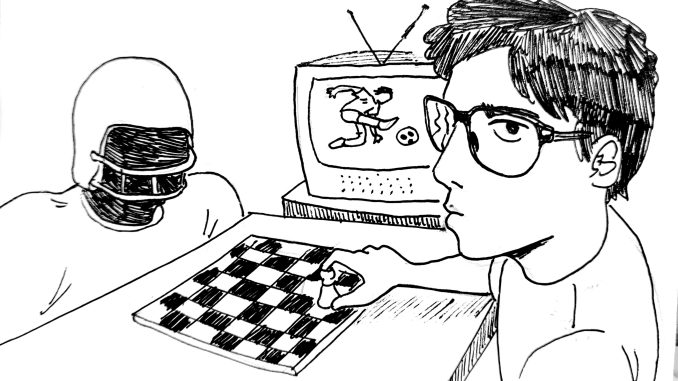

Checkers is a game, football is a sport. If sports and games are indistinguishable, then what are we doing? Their mistake is to think that if football is a game in the same way that checkers is, football doesn’t matter. But no: checkers matters just as much as football if enough people watch it. It’s not the game itself, but the social experience.

It’s a widely held belief that in order to be a proper “sport,” you have to fulfill some invisible requirement for physical exertion. This is a tool to separate different sorts of game enjoyers. Though a football coach and Chess master may teach at the same university, they would never be put in the same department. We’ve decided that they are cut from different cloths.

But imagine a game where, for ninety percent of it, you are playing checkers. As you do, a team of people are in position to play football. Every once in a while, you do something in checkers that requires the people on the field to play two minutes of football, then they stop, and the checkers start again. Is this a sport? Is ten percent running around, ninety percent waiting and thinking enough? Because that’s baseball. Most of the time, when it gets to your turn in baseball to swing the bat, you don’t even hit it.

I have met one person who says that baseball is “not a sport.” If your earnest definition of “sport” does not include baseball, hit the showers. If baseball isn’t a sport, we’re all doomed. We love to build these arbitrary walls around things to keep them ours, and to separate them from the things that others like. It’s all malarkey.

Chess is a sport not because you are thinking so hard that it exhausts you as you play it. Chess is a sport because it has recognized official ranked play. I submit that if something has official ranked play (on any level), it’s a sport. Why not? We have unlimited uses of the word.

Such a linguistic shift may aid in this asymmetric divide between game players. The idea that football is categorically totally different to a board game like Settlers of Catan is fictitious. We all need to wisen up to the fact that we are built to love games of all sorts.

They all mean something, they are each worth our time, so long as we experience them in good company.