By Michela Arlia

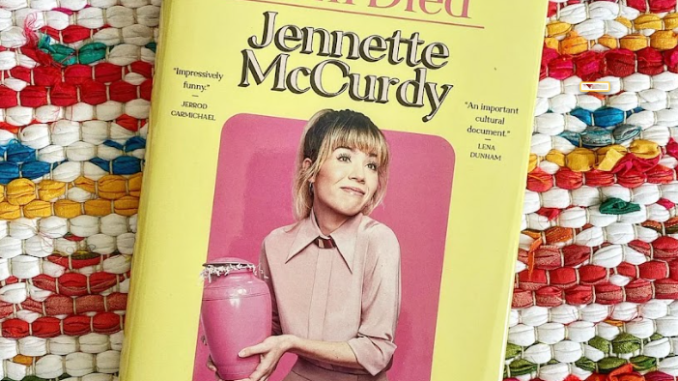

Jennette McCurdy’s heavy novel “I’m Glad My Mom Died” was a book I set out to tackle reading, albeit I was very late to the game.

The only thing worse than producers, creators, and big-time executives in the Hollywood industry has got to be the moms.

Think of it this way. The child actor is the talk of the town and is splattered onto every billboard and commercial – they are just the head. The moms, though, are the neck. If the children are the head of this corner of the industry, mothers are the neck. Though the face is what you see, the neck controls everything but the expression.

This may be my nerdy psych background poking through, but a mom is often their daughter’s first teacher. This job is tedious, and one wrong move could set the little girl up for a daunting life path.

I’ve had the typical signs of abuse drilled into my head for the past three years in counseling courses, but I have learned more about it in this one novel than a bachelor of science degree could ever teach me.

Jennette, I heard you. Loud and clear.

For 320 pages, I was constantly baffled at the blatant sexual, verbal, physical, and psychological abuse being put onto this child. The excellent use of tone allowed me to picture these vignettes from the viewpoint of the age McCurdy was when experiencing these events. She made me want to scream through the pages as she effectively put me through her mindset, all while making it impossible to help her past self out of said events.

There should be three mandatory classes every undergraduate student should take: human anatomy, ethics, and child or developmental psychology. Universities neglect fundamental values of knowledge, trading it in for over-the-top core requirements to make a quick buck.

How are we, as college students, expected to go out in the world and create a better future for the children of our nation if we can’t even understand them at the age of four?

People like McCurdy write these novels not only as a therapeutic outlet, but for awareness. She is the brave soldier who came out to share her truth and recovery, and to see the masses of people who come out of the shadows in solidarity further illustrates that candor surrounding abuse in Hollywood. Despite this honesty in sharing trauma, these abuses are still stigmatized, even here in Brooklyn.

30-40% of children are abused by a member of the family within their home. It often comes with the notion that a parent is only helping or protecting their child. Lies.

McCurdy herself experienced in-depth “medical examinations” of her body by her mother until age sixteen, sharing showers with her much older brothers so their mother could wash them and get their hair “just right.”

She stunted her own pubescent growth with the help of her mother. She was told to calorie count, inciting anorexia, at age eleven in order to stop herself from developing the reproductive parts of her body, just to book younger roles. And there is much more where that came from.

Claims have been made that the stigma surrounding mental health or child abuse has been removed or that major advances have been made in confronting abuse, but that is a bold-faced lie if I’ve ever seen one.

In fact, if reading parts of this made you uncomfortable, then the stigma is ever-present.

We are not protecting our children, and the first defense against occurrences like this is knowledge.

So make this memoir a required textbook in a college course because we learn best from experience. And let’s make some actual changes in the discussions around abusive relationships.