By Kate Dempsey

“Women’s wars are not men’s wars.” In Cynthia Enloe’s new book “Twelve Feminist Lessons of War,” the internationally renowned author dives into why, during wartime, women possess unique disadvantages and will continue to do so unless more equitable change is brought about.

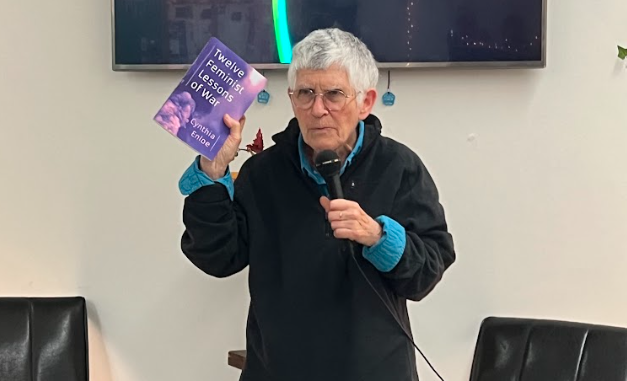

Brooklyn College’s Department of Women’s and Gender Studies, the Institute of Gender, Law, and Transformative Peace Initiative at CUNY School of Law, BC’s Women’s Center, and other departments hosted Enloe on Oct. 30 to discuss her newest release. Enloe, a political theorist, feminist scholar, and professor, has studied women around the globe and their roles in becoming “resistors” to the structural force of patriarchy.

“Twelve Feminist Lessons of War” draws specifically on the experiences of feminists in Ukraine, Myanmar, Somalia, Vietnam, Rwanda, Algeria, Syria, and Northern Ireland during wartime. The book examines the disparities faced by women and how they are often made invisible during times of conflict. To resist is for women to continue to advocate for women’s rights in war, Enloe explained, adding that it was essential that she drew on the women’s experiences that were shared with her when writing the book.

“These are people who take me places to make sure that I really understand what happens in war and who tries to resist it […] so that I could at least see what it takes to resist,” Enloe said.

In Enloe’s book, she highlights that discourse about war oftentimes “blot[s] out complex gender dynamics”; terms like refugees and soldiers do not specifically state whether it is men or women who make up these groups. In order to utilize a gender justice lens of war, language should be more gender-specific in order to fully contextualize a conflict. Instead of “refugees,” we should ask, “Are women more likely to be refugees than men?” Instead of “soldiers,” we should ask, “Are men’s experiences as soldiers different from women’s?”

The book highlights the numerous wartime disparities between men and women. While both are forced into refugee status, women often struggle worse with higher rates of illiteracy, rendering them unable to read directions. Both men and women are paid for work, but with lower rates of pay for women, they are the ones unable to buy supplies in wartime. Both men and women are citizens of a country, but it is women who are considered second-class citizens to men and, therefore, barred from autonomy in wartime.

A focus in Enloe’s work is the role of nurses, one often given to women based on historical presumptions of women as caregivers. The work is important, but it is governments who often take advantage of women when assigning this role, which leads to less upward mobility when the conflict has ended.

“Every government wants to lower two things: they want to lower the actual costs of waging a militarized operation, and that means they want women as wives and mothers to do the unpaid work of caring for the wounded. The second thing that governments want is they want all of us to imagine that wars are cheaper than they are,” Enloe said. “If we all actually followed every wife and mother who took care of every traumatized soldier or severely wounded civilian that was a result of war, if we actually followed what those women do, sometimes they give up paid work so that they can be full-time carers of the wounded. And that’s not just until the war ends; it is for months and years.”

A pertinent topic was brought up towards the end of Enloe’s book talk: the state of violence occurring globally right now. As news media floods images of violence in Gaza, Sudan, and many other regions, an enormous amount of violence is being waged against women. Enloe advocated that, as citizens of the world, we all need to continue to do our part to meaningfully engage – to not let the violence overshadow those suffering from it.

“We’ve got a lot of horrible conditions of collective violence around the globe now. And we all are in some ways, because we are all on this planet together, have to be able to engage usefully, valuably,” Enloe said. “And as hard as it is, stay conversational because that means you are a citizen, a citizen of the world.”