By Paulina Gajewski

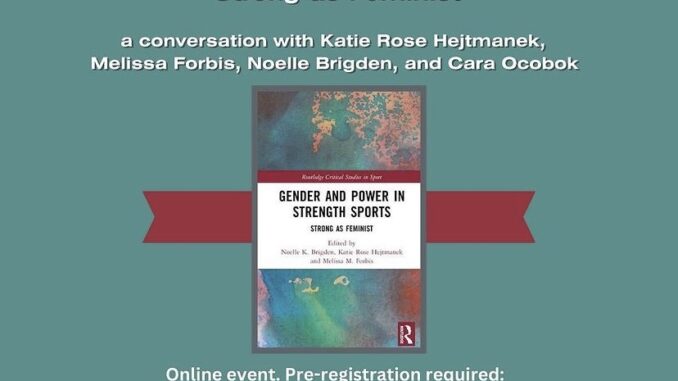

The Wolfe Institute held a virtual conversation on Tuesday, Nov. 28, that tackled the frameworks of gender and power as they fit within the world of sports and fitness. This was the last in a series of events that celebrate the releases of new books by Brooklyn College faculty. The book, titled “Gender and Power in Strength Sports: Strong as Feminist,” delves into the personal experiences and works of research within sports communities.

The book aims to question the ways in which participation in strength sports constitutes an insurgent practice. Women taking place in these fields regenders the traditional pillar of masculinity that they are dominated by. Not only does the book question such ideological issues, but it also questions the structure of the actual material spaces in which strength sports occur, as well as the social and political contexts on which these practices happen.

Noelle Bridgen is an associate professor in the department of political science at Marquette University, and is one of the book’s co-editors. Her research focuses on trauma-informed, community-engaged projects that promote feminist social justice. Bridgen’s history in the sports field stems from physical rehabilitation after an accident. To gain strength back, she entered fitness initiatives, specifically powerlifting.

“I began to view my body as a source of strength rather than beauty,” Bridgen said during the talk. “I found it was really reaffirming my identity as a sort of ritual.”

Bridgen later returned to El Salvador to continue her work on violence and borders. Her research, as documented throughout the book, attempts to understand trauma as the way the body responds to and ultimately wears political oppression.

The majority of information in regards to fitness is fed to people through social media. Bridgen reinforces the idea that such information is often loaded with sexist, ableist, racist, and ageist thoughts. These often perpetuate forms of internalized coloniality.

Strength is a word that when used is often used to describe masculinity, especially physically, as Melissa Forbis, a cultural anthropologist that teaches at both BC and NYU, stated. “When we [women] get told we have strength, it’s about how much we can endure. We have to break through this idea.”

Co-editor Cara Ocobock is the director of the Human Energetics Laboratory at the University of Notre Dame, as well as the assistant professor of anthropology there. Ocobock’s studies took her to the Rocky Mountains, a feat of great strength considering she had to carry both hiking equipment along with her research equipment. Ocobock would lift and do cardio to gain strength for such an expedition, and in doing so, she experienced the toxic attitudes most male-dominated gyms had towards women, projecting their ideas of limitations of women’s bodies into the space.

Editor Katie Rose Hejtmanek, associate professor of anthropology: children and youth studies at BC, imbued her portions of this book with her research. She started off researching the cultural processes of self-transformation in a mental institution for children. Her research also focuses on CrossFit gym and strength sport collectives, along with actually competing in Olympic weightlifting.

Forbis researches social movements, indigenous rights, and gender and the state. Her interests in sports studies grew out of participation in transnational social justice soccer networks. Her current research examines the “ways in which strength and powerlifting practices have become tools to build individual resilience and strength for LGBTQ communities,” as she told the audience.

The works and research of these women influenced and are very much directly in the book itself. Strength sports, in particular, are a framework through which gender can be studied. Such sports have become integral to the perpetuation of the patriarchy, but also, in recent years, a resistance to it.

The book itself is divided into three sections: “The Public Body,” “The Disciplined Body,” and “The Social Body,” and the writers all come from a variety of disciplines and regions. In between the sections are interludes, which include experiential stories that link to the pieces, and aim to understand how gender and power fit into the world of sports.

“Lifting became a really wonderful way for me to shift the focus to not on what my body looks like,” Forbis said, “but what it can do.”