By Paulina Gajewski

Humming floats across vaulted stone ceilings as men in long robes saunter between archways. A chill weaves its way through the courtyard, carrying itself with grace throughout a day spent in silence. Perhaps the chirp of a sparrow may echo, the shuffling of feet across stone drowned out by a flowing fountain across the hall. The Met Cloisters, an enclave of nature amidst the sprawling city landscape of Manhattan, provide a quiet retreat from the constant buzz of our world while simultaneously immersing us in history.

History professor Lauren Mancia spearheaded a series of conversations at the Cloisters, the most recent of which took place this past Friday, Feb. 2. Specializing in medieval Christian devotional practices and monasticism, the cornerstone of her research aimed to investigate the lived realities and experiences of historical subjects.

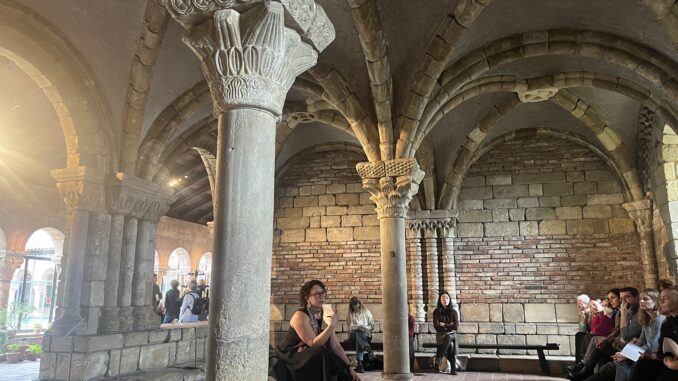

The museum itself sits atop a hill as the guests follow winding paths through a forested landscape. The first portion of the experience required immersing the guests into the life of a monk. Students were greeted by the architecture of the chapter house from a French monastery founded in 1115 and eventually sold and brought to New York in 1932.

This tended to be the daily meeting place, in which monks and nuns would sit on benches around the walls, and guests were seated in such a fashion. To take part in the immersion, guests would relinquish their phones, placing them into a basket as they uttered the words, “I long to be emptied of myself.”

Such would have been the ascetic life of monks hundreds of years prior. Guests were also instructed to remove anything that they felt distracting or tempted to remove their focus from what was to soon be a period of silence and reflection. Passed around the room were sachets of smelling salts, scents meant to engulf the guests in the activity. The goal of such an act, as emphasized by Mancia, was to explore how she could relay information to students but also other scholars through performance art. “What I find valuable is the way that this practice ignites the audience and transforms us from spectators to active, vulnerable witnesses,” she told The Vanguard.

Guests were handed booklets with a variety of tasks and readings from scriptures that monks would focus on. Once the twenty-minute period of silence began, guests were instructed to focus on the provisions in the booklet and walk around the cloisters in complete silence, refusing to succumb to distractions. Some guests gravitated towards the space of the church, others gravitated towards seating arrangements around the cloisters.

Once the period was over, guests were gathered back into the chapter house, awaiting reflections and discussions on their experiences. For such an individual activity, it was difficult not to feel as if it was a communal experience.

“Professor Mancia’s solitary meditation exercise was a great introduction to the ascetic aspect of Medieval monasticism,” reflected BC student Caren Ghali. “For twenty minutes, one could truly experience how difficult it was for medieval monks to tune out the world around them and tune into the divine.”

Historians and scholars have chosen to portray historical narratives and make such claims through detached readings of sources of the past. This experience was a shift in how one might experience and tell such histories. “We make ourselves immune to the effect of ‘doing,’” Mancia stated.

The trip taught students that they may learn through disembodied readings of history, especially when one may fall into the trap of projecting modern ideals and expectations onto historical subjects so far removed from us through time. Through such performance art, they can catch a glimpse into what the actual lived experience was for both the individual and the collective.

The world of the past often seems distant from the cultures and lives of those who are different. The goal of experiencing medieval monasticism is to provide a glimpse into understanding others, breaking down the barriers of reluctance towards other cultures and lifestyles, and jumping in with both feet into the acceptance of humanity as a whole, rather than divided.