By: Serena Edwards and Eddy Prince

On Dec. 3, the Wolfe Institute held a virtual discussion with Robert L. Hess Scholars Melissa Murray and Russell Jeung. During the event, both speakers and attendees discussed what “justice” means to them and how to achieve it in these times.

Justice has long been tied to historical inequality, as is the case with the Jim Crow laws from the 1800s. How do we reconcile the tension between individual justice in the courts and collective justice within our society, especially when these inequities persist?

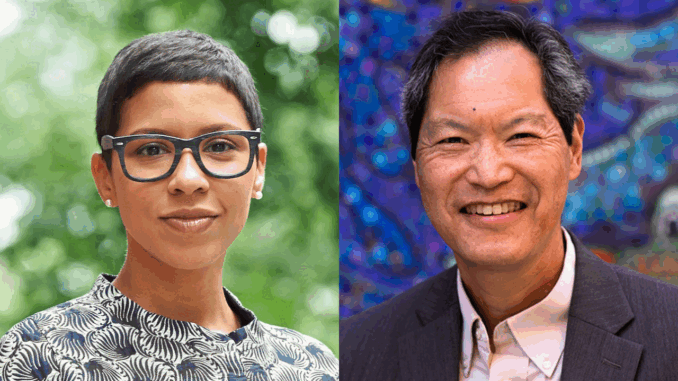

Murray is a legal analyst for MS Now (formerly known as MSNBC), a law professor at NYU, and co-host on the podcast “Strict Scrutiny,” where she breaks down Supreme Court rulings and other legal culture. She served as the Hess Scholar for the 2024-2025 school year, which was previously reported by the Vanguard.

Jeung is an Asian American studies professor at San Francisco State University, co-founder of Stop Asian American and Pacific Islander Hate, and an author and producer of a plethora of projects. He currently serves as the Hess Scholar for the 2025-2026 school year.

Gaston Alonso, the director of the Ethyle R. Wolfe Institute, moderated the conversation, asking how they were introduced to the topic of justice and how they have fostered it through their careers and upbringings.

Murray started the conversation, highlighting the role law plays in the lives of people of color.

“I think you can not be a person of color living in the United States without understanding the role that law, especially constitutional law, has played in making society one that we are participating in the way we are now,” Murray stated.

She acknowledges that times have changed for people of color. “All you have to do is look back 250 years. You can see how different it was for people who looked like me […] Much of the change really broke by way of law.”

Murray also spoke about how having an immigrant family changed her perspective on law.

“As someone who grew up in an immigrant family in the south, it was just clear to me from the beginning that so much of my life had been made possible through law.”

Jeung, who worked closely with marginalized communities, spoke on the impact these communities had.

“Community-led justice looks like, for me, when people feel safe and secure wherever they are. Going beyond a defense of one’s rights that entails everyone taking responsibilities for each other and doing what’s right,” Jeung told The Vanguard.

Jeung defined his morals and what they look like from a personal standpoint.

“For me, doing what’s right involves making sure people are housed, making sure people are fed, and making sure people have the right healthcare,” said Jeung.

Jeung shared advice for those who are beginning to become independently involved in their community.

“I think right now people in our polarized society don’t want to hear each other or empathize with one another, so sharing stories is really important to change people’s hearts and minds.”

Jeung states that it doesn’t have to be a big initiative at the start; it can start right at home.

“People can begin to tell their stories to their families and to their friends, so we have a greater sense of how people are hurting and how people can comfort and support one another.”

Both Murray and Jeung emphasize the importance of fighting for justice collectively rather than individually.

“The American system is very, very individualistic, not something that focuses on group rights in a really focused way. ” said Murray.

Murray explains that at times it is not about you and the group you identify with.

“If you think about American anti-discrimination law, it is about what happens to you as an individual and then only tentatively about what might be happening to you because you are part of a group,” stated Murray.

Jeung followed it up with his thoughts on the divide between individuality and collective activism.

“I think we can balance the need to protect individual rights. We also need to recognize that public policy affects all groups. Public policies affect and treat certain groups differently than others,” said Jeung. He continues by explaining further that we can combine individual activism with collective activism. “How can [individuals] work and collectively break policies that target entire groups? We need to protect individual rights, but when groups are negatively impacted or mistreated, then we need to find group solutions.”

Justice can be achieved through cross-racial activism, especially through marginalized groups. “The Oak Park Story,” Jeung’s short documentary about a legal battle between immigrants and a landlord in Oakland, California, showed how, when people band together, justice can be achieved for all marginalized communities.

“We have to organize around common issues that we all experience and feel,” said Jeung. “I don’t think the Cambodians were organizing as Cambodians, or the Latinos [as Latinos] […] we all saw ourselves as neighbors who faced similar housing conditions. That gave us our solidarity. I’m proud that we stood up together,” said Jeung.

“Multiracial organization isn’t about organizing [as a certain race]. It’s partially that, but it’s also, we need to relate beyond our identities and connect along our common personhood and around our shared issues,” Jeung concluded.

During the talk, Alonso pitched the question of whether or not justice can actually be achieved as a society. “I think the alternative to not pursuing justice is apathy, it’s cynicism,” said Jeung. “We don’t know if we’ll ever achieve justice. But we pursue justice because it’s the right thing to do.”

“I like the idea of justice as a constant work in progress,” Murray followed up. “[Justice is] something we’re always working towards, and we’re never entirely finished with the project of achieving justice.”

Jeung argued that justice is often a product of circumstance. “I’m a fifth-generation American,” said Jeung, “but I was raised in a very Asian environment. And I have family members who grew up in the same family, but they may have different opinions and perspectives. We all have our own histories which come from our own circumstances, that shaped how we see the world and how we try to make change. Our individual circumstances are often our gifts. Everybody is different, and everyone has their own perspective.”