By: Mars Marte

On July 25, New Yorkers awoke to an emergency announcement from the city’s Health Department declaring an investigation into an outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease detected in Central Harlem and infecting five people.

Legionnaires’ disease is a severe strain of pneumonia that originates from the bacterium Legionella, which can grow in warm water systems. This outbreak started from Legionella residing in cooling towers often found sitting atop the city’s infrastructure, such as apartments and hospitals.

The effects of Legionnaires’ disease can range from a fever and cough to, in some cases, death, according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC).

The severity of the outbreak is evident and harkens back to a decade, when the city was battling Legionnaires’ disease for the first time in the South Bronx. The results were disastrous, leaving 138 people sick, 16 of whom succumbed to the sickness.

According to Dr. Jay K. Varma, who served as an incident manager during this outbreak, “Experts had warned that cooling towers were a likely source of recurrent Legionnaires’ outbreaks”.

Despite the warnings, the city had made no attempt to protect the most vulnerable group, low-income families. The systematic separation of the South Bronx only fueled the flames of the Legionnaires’ frenzy of 2015.

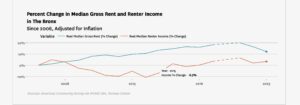

A study conducted in 2023 by the NYU Furman Center revealed that the poverty rate in The Bronx was 27.9% in 2023, compared to 18.2% citywide. While this comparison is based on recent statistics, a similar graph found within the same study analyzing the change in median gross rent and renters’ income shows that the disparity highlighted in 2023 was pre-existing.

Only after the loss of many lives, the city responded by enforcing regulations such as requiring that buildings register cooling towers with the Health Department, which will then test them quarterly (every 90 days).

Yet the regulation proved futile when its enforcement became inconsistent in impoverished neighborhoods.

At the beginning of the year, inspections of the city’s cooling towers fell dramatically, according to the Gothamist. While inspections were falling, the department had received a 30% boost in funding, according to the Independent Budget Office.

With inspections reaching low rates, communities such as Central Harlem find themselves at greater risk.

The study previously conducted in the South Bronx by NYU was now carried out in Central Harlem. The results showed that “the poverty rate in Central Harlem was 28.6% in 2023 compared to 18.2% citywide.”

It is apparent in the response to the outbreak that poverty-stricken communities are greatly susceptible to city neglect.

The city announced the breach on July 25 and had only specified that five zip codes should be on the lookout. Over two weeks after the initial announcement, the city confirmed where the impacted cooling towers were located.

On Aug. 14, the NYC Health Department reported that “12 cooling towers have tested culture positive on 10 buildings for live Legionella bacteria”.

Of the 10 buildings that were confirmed to be the source, four were city-owned buildings. Another building associated with the cluster was the Public Health Laboratory construction site that had not yet registered the cooling tower, which is required before initial operation, as reported by Maya Kaufman from Politico.

Other buildings impacted by the bacteria had received a notice sent July 1 by NYC Health and Hospitals, informing the construction companies about the possibility of Legionella developing in the cooling tower.

On Aug. 29, the city declared the disease’s reign over, which resulted in 114 cases, 7 of which were preventable deaths, and 90 people were left hospitalized, according to The Guardian.

It’s no coincidence that the areas that suffered highly from legionnaires are communities of color.

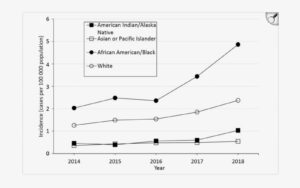

A graph made by The PMC, compiled of information available on the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System, reveals that people who identify as African American and/or Black are at higher risk of infection with Legionnaires’ disease.

Those impacted by the diseases are rallying behind Ben Crump, a prominent civil rights attorney, who announced a lawsuit against contractors, claiming they had failed the people of Central Harlem.

When questioned about the infection, Mayor Eric Adams responded that there had been “clear procedures on inspection.”

The Guardian discussed the Adams administration’s new proposal in response to the outbreak, which included increasing the testing period from every 90 days to 30 days.

No matter how clear a procedure may appear, if there is no enforcement, the policy sinks. The people of Harlem, and all communities of color and in need, deserve a city that promotes health, not illness.