By: Khalailah Bynoe

When you walk through The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s (MET) “Witnessing Humanity: The Art of John Wilson” exhibit, you can feel the emotions that Black American Artist John Wilson wanted to evoke. Wilson created art for more than six decades, experiencing many pivotal moments in our history, including the civil rights movement and the Vietnam War. Wilson captured these moments in time through various media, including drawing, painting, printmaking, and sculpture.

“I am a Black artist. I am a Black person. To me, my experience as a Black person has given me a special way of looking at the world and a special identity with others who experience some injustices […] Themes I have dealt with are not because I sat down and said I wanted to make a political statement, but because of emotional experiences.” Stated by Wilson.

The exhibit was organized into eight themes, each displaying various artworks by Wilson. The eight themes are as follows: Martin Luther King Jr., Fatherhood and Family, Violence, Paris, Mexico, Envisioning Humanity, Home and Hardship, and War. Although each theme brought along different uses of color and compositions, the message Wilson wanted to tell was the same. He wanted to empower African Americans.

“Wilson believed his imagery validated the humanness of African Americans, not thought to be worthy of beautifully dignified, poignant portrayals,” said Leslie King-Hammond, Founding Director, Center for Race and Culture, and Professor Emerita, Maryland Institute College of Art. Black fatherhood is often spoken of in a negative light, but Wilson created many artworks that portrayed fatherhood positively.

An example is “Father and Son,” a charcoal drawing showing a father holding his son in a loving, warm embrace. A secondary charcoal drawing, “Study for Child with Father,” was created during the time of MLK’s assassination. Wilson wanted to instill hope for the future generation of black children despite the troubling times. This drawing was also related to a lithograph, a special form of printmaking, that Wilson made for the Boston-based group “Artists Against Racism and War.”

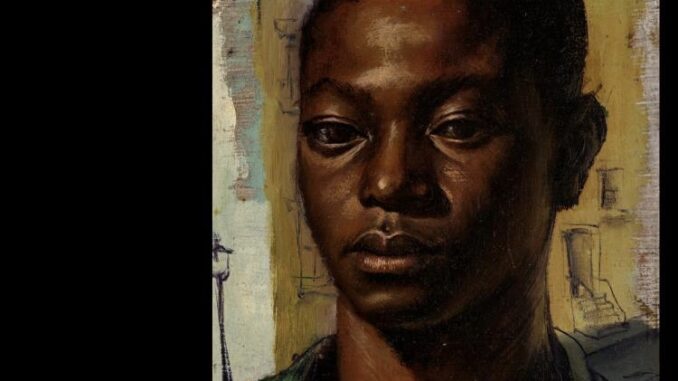

“Black Boy,” a lithograph Wilson created based on a drawing he had made in Mexico a decade prior, was inspired by writer Richard Wright’s 1945 memoir. “A man of truth […]. Wright’s words gave me a whole conception about what was happening to Black Americans. And it was a confirmation for me. I wanted to create images that would be as powerful as what he had written; to do with a line what words about a man I wanted to do it visually,” stated Wilson.

Wilson lived in the Bronx and Queens for seven years with his family in the mid-1960s. During his time in New York, he taught art in middle and high schools in New York City public schools. In the watercolor painting, “Bronx Landscape,” he captures the essence of a typical NYC apartment building’s exterior. The piece is vertical, including the details of bricks and even the fire escapes that many New Yorkers have as an alternative to a balcony.

One particular painting, “Incident,” displayed the violence Black Americans faced in the South. Tusche, a greasy, blank ink used in lithography and oil painting, was used to create this piece. The expression on one of the black figures’ faces struck me the most with the way his eyes widened in fear, with the juxtaposition of raising his fist to defend himself.

“This business of the terror that was used to keep Black people in their place really worked. I wasn’t born in the South, but the South was a microcosm. I mean, there’s actual physical lynching and murder in the South, there was psychological lynching in the North […] I heard someone make a speech once in which he said, ‘Well, this lynching and the threat of lynching is what keeps Black people in their place.’” a quote from Wilson.

The exhibit shared many powerful messages. Wilson wanted to be a part of art history and to show the world what being black meant to him. “I drew scenes of the world around me which reflected the sense of alienation I felt as a Black artist in a segregated world.”

This exhibit will be on display until Feb. 8, 2026 and is currently held in Galleries 691–693 of the MET.

For more information regarding future exhibitions at the MET, visit their website at https://www.metmuseum.org/.