By Gabriela Flores

The intersection between race, gender, sexuality, and all other aspects that build identity have often shaped human experiences. As times have changed, more discussions of the complexity of identity and how it’s perceived in different communities have come about. On Oct. 12, Brooklyn College’s Wolfe Institute hosted a panel on these topics, along with the ongoing challenges the queer Black community faces.

“You have to continue bringing these conversations of queerness within your own circle, within your family, within the structures that you see daily,” said Kaneita Marcelin, a BC student, activist, and artist, during the event. “Yes, I award every Black queer person that’s been able to succeed but there’s those of us that are still dying; there’s those of us that can’t find housing; there’s those of us who can’t find jobs because of our queerness.”

Marcelin and three other panelists joined the conversation that was inspired by the current Hess Scholar-in-Residence Barbara Smith, a lesbian Black feminist who encouraged reflections on the intersectionality of patriarchy, heterosexuality, racism, and other structures. Together, moderated by Professor B Lee-Harrison Aultman, the panel shared their anecdotes and opinions about queerness within the Black community — and how too often it is shunned or unaccepted in different contexts.

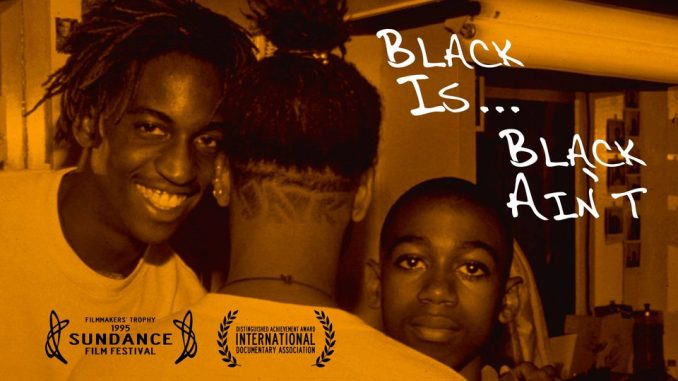

In doing so, the panelists and participants who tuned into the virtual round-table saw clips from “Black Is…Black Ain’t,” a documentary directed by Marlon Riggs that delves into the very themes of queerness, Black identity, masculinity, and femininity. One of the vignettes shown featured Smith discussing how she was attacked in a 1978 Black Women Writers conference at Howard University, a historically Black institution, for her essay critiquing how Black feminism at the time ostracized Black lesbians. In the clip, Smith recounted how the audience, who were mostly Black women, had one member commenting that to accept homosexuality in the Black community would mean endorsing “the death of our people.”

For some of the panelists, this notion of many cisgender Black women not accepting queerness within their community persists today.

“I feel that a lot of cis Black women they create, they have perpetuated, this homophobia, the transphobia, that currently exists in the Black community,” said panelist Kiara St. James, the founder and executive director of the New York Transgender Advocacy Group. Later in the discussion, she noted that often many cis Black women would enforce heterosexuality, and in turn, exercise homophobia or transphobia.

Smith, who was on the call, chimed in to recognize the fruitful ideas St. James and other speakers brought to the conversations she and her fellow activists began decades ago. In doing so, Smith reflected on the “brilliance” of their queerness.

“That’s where being willing to go outside the expected patterns, then think of new things, even if you’re in nanoscience or something,” Smith said during the event, “that queerness really uplifts our capacity to dream, to create, and I’m just feeling so excited about being affiliated with Brooklyn College.”

The following documentary clip discussed Black masculinity, where Riggs implemented some history of Black people in America. According to the clip, Black men were previously seen as weak or “child-like” in comparison to Black women. Once talks and actions related to Black power came into fruition, Black men were able to have their “redemption,” and so too did Black women presumably — but in actuality, not every Black woman and their ideas for equality in the Black community were accepted. Instead, those like Smith who are queer and vocal about “speaking truth to power,” were often ostracized for their ideas and queerness. After the viewing, the panel’s moderator asked the speakers if they think there is a linkage between “sexual politics and racial politics” as Smith previously argued.

One panelist, Stephen Winter, an award-winning filmmaker and artist, noted how “sexuality and politics have never been unlinked.” He later made reference to “Jason’s Lyric,” starring Jada Pinkett, which was given an R rating for a love scene that the film contained. Winter argued that there are double standards placed between Black and white filmmakers and their productions.

“The hypocrisy of how they see Jada Pinkett making love over any other white woman is the thing we have to fight that is an illustration of that comment – the sexual is always political when it comes to Black people,” said Winter.

After each panelist shared their perspectives and lived experiences as queer Black people, they ended the discussion on a note of what could be done to remedy the divisiveness still present in their community that alienates queerness. At the core of many of their responses was a call for holding more discussions to understand Black queerness and the importance of ultimately accepting the different complexities of the community at large.

“When I think about community as ‘Black people reconciling differences with each other,’ I think first and foremost labor,” said Joe Baez, a BC alum who is now studying as a graduate at George Washington University. As she survives academia and its predominant whiteness, Baez has found and formed part of a support system of other non-white academic thinkers that exchange acts of kindness, or “labor,” as she puts it.

“I think communion to me shows how much labor is required to be with someone because it’s the notion that you are connected to someone because of a shared identity is not it – it requires labor to be with someone, to make sure you are doing right by each other,” Baez said during the event.

For St. James, it’s important for Black queer people to also make their presence known in cisgender spaces despite any challenges or pushback they may receive for being queer.

“What we have to find a way of doing is to continuously be in communication with one another,” St. James said. “And for us queer Black people – be brave enough to go into those cis Black spaces even if we’re the only queer Black person and have these conversations that, ‘I’m just as Black as you are. My queerness does not make me less Black.’”