By Lina Mazioui

An exhibition displaying Maxime Du Camp’s photography debuted at The Metropolitan Museum of Art on Oct. 23. The exhibition, titled “Proof: Maxime Du Camp’s Photographs of the Eastern Mediterranean and North Africa,” highlights the museum’s collection of the earlier photographs which were not published in the French photographer, journalist, and explorer’s famous book “Égypte, Nubie, Palestine et Syrie,” as well as a previously unseen handbound album.

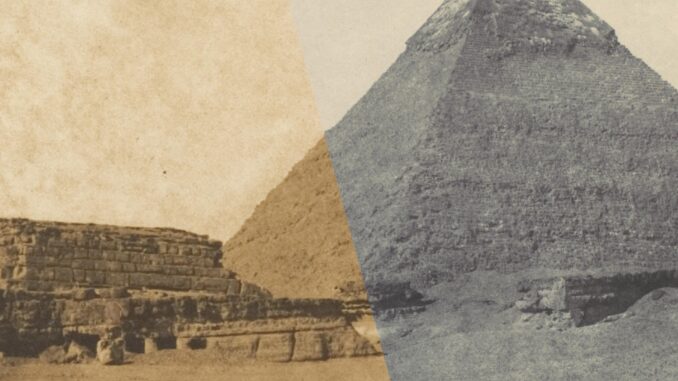

With 125 carefully captured sights, “[…] its salted paper prints are rendered in cool, gradated tones that one contemporary critic described as ‘vaporous gray,’” which had “arguably established an aesthetic standard for documentary photography,” as explained in the Met’s overview of the recently opened exhibition.

From an artistic standpoint, the Middle East was shrouded in attractive mystery and fascination to the Western European elite of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. From excavation to illustration, the “Orient” was an exciting subject that garnered attention from European consumers. The “Orient” is a term that began to be thrown around during this period, a fictitious world curated by the Western fantasies and assumptions about the broad region that is North Africa, the Middle East, and Western Asia.

The invention of photography in the early 1800s allowed more space for such stereotypes and false assumptions to fester. Though photographs do show a tangible world, it doesn’t mean that it is reality. Many European photographers at the time intentionally composed their photographs and showed specific parts in their images in order to support their Orientalist agenda.

One such artist was Du Camp. His book “Égypte, Nubie, Palestine et Syrie,” published in 1852, revolutionized both photography and travel in Europe during the nineteenth century. As one of the first photographically illustrated books, all those intrigued by the unfamiliar world he presented through photographs flocked to see his work.

The archaeological sites featured throughout his book up until now were only seen through the images created by an artist’s hand, where details may have gotten lost in translation. Now, people could discover them as if they were standing right in front of the wonders themselves.

When Du Camp traveled to the Middle East, he took more than 200 pictures, choosing to only publish 127 of them; 75 secrets were left unshared. Along with the “lost” prints, significance also lies in the proofs Du Camp privately printed before publishing the final prints in his illustrated piece.

The earlier proof versions are toned warmly, the raw sienna and ochre hues emitting a sense of warmth and radiating the sunlight which so strongly beams down onto the landmarks in which Du Camp traversed. These warmer prints are strikingly different from the final ones, which were toned specifically to have cooler values. When compared to the published versions, one cannot help but notice the stark differences.

“Proof: Maxime Du Camp’s Photographs of the Eastern Mediterranean and North Africa” explores that inevitable question of secrecy and decision. By putting the previously private works on display for all to see, the exhibition acts as a rebellion against the assumptions the West makes about the unfamiliar world and simultaneously brings light to the world that Du Camp had genuinely seen on his voyage so many years ago. Through the contrast of the published prints and the earlier proofs, the viewer discovers the complex implications of nineteenth-century European photography and Orientalism.

Du Camp’s book focused on the ancient monuments and more dated sites of the countries that he had visited, but the earlier prints showcase modern (at the time) cities that flourished with life. Du Camp understood the expectations of his European peers and viewers, who wanted to see the “Orient” they had built in their minds: archaic, arid, and exotic archaeological scenery. Therefore, Du Camp gave it to them. What he did not show was the truth of the vast region, with bustling city streets and people of a variety of different cultures and art.

Though Du Camp’s earlier prints are still, of course, convoluted with his inevitable European bias, they hold a certain reality that is not seen in the final prints published in 1857. By seeing the curation process of his published work, viewers can understand the mindset of many artists at that time, who were extremely aware of what their society expected in their work and made the effort to cater to those temperaments, but were at the cost of the inhabitants of the world, which they had found so fantastical.

Du Camp’s exhibition will be available to view at the Met with general museum admission through Jan. 21.