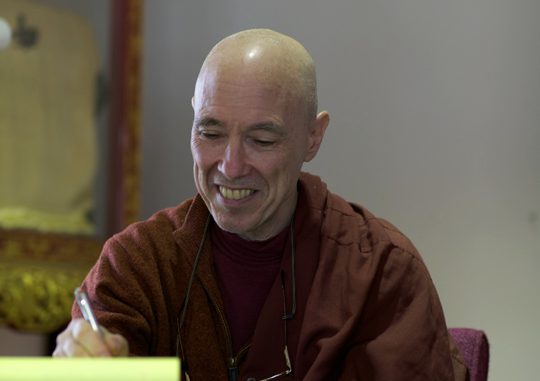

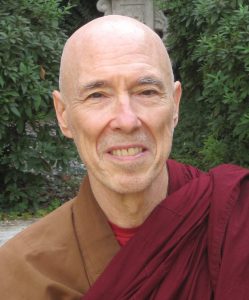

As a young man, Jeffrey Block was your average Brooklynite, working as a door-to-door salesman, and, like many of his friends at the time, attending Brooklyn College, where he graduated in 1966. 53 years later, he has addressed the United Nations, has been published more than a dozen times, and is one of the most prominent Buddhist teachers in the United States.

Block, now a monk, and known by his ordination name of Bhikkhu Bodhi (Bodhi meaning enlightened), currently resides in Chuang Yen Monastery in Putnam County, New York. The Monastery is a 225-acre complex adorned with temples and gorgeous views – not to mention the largest indoor Buddha statue in the Western Hemisphere.

It’s a far cry from where Bodhi grew up in Borough Park, Brooklyn. Born in December of 1944, just as the U.S. was beginning to turn the tide in World War II, he and his sister were raised by a customs worker and a bookkeeper not far from New Utrecht Avenue and 52nd St. Although now his life revolves around a spiritual lifestyle, his upbringing not quite the same.

“We were Jewish by a sense of cultural and ethnic identity,” he told the Vanguard through a video interview.

His childhood was reasonably normal for a young Jewish boy in the 50s. He went to public school, got Bar Mitzvahed, and attended Brooklyn Technical High School before realizing he had no inclination towards the science- and engineering-based curriculum pushed at Brooklyn Tech. He left in his sophomore year and finished his high school education at New Utrecht High School, but at the time he still didn’t have a path in mind.

“I didn’t have an idea of what I wanted to do,” he said.

After spending two years at Harpur College (now SUNY Binghamton) post-graduation, Bodhi decided to take some time off from his education and figure things out. While taking his one year break he worked as a door-to-door salesman for the Fuller Brush Company selling brushes along with other personal care and household cleaning products.

“It was an interesting experience,” he said, smiling.

After having enough of selling brushes, he decided to restart his education and attend a reasonably small (and then, very cheap) local public institution called Brooklyn College.

“It’s where my friends at the time were going at the time,” he said.

He arrived at BC in the middle of the 60s as a philosophy student with an interest in reading and learning about the wider world. While at BC he got involved in some of the anti-war protests that were popping up across college campuses as the Vietnam War began to escalate.

“I was opposed to the military involvement in Vietnam, which I realized was leading to the violent and unnecessary death of thousands of people,” he said. Despite his anti-war sentiment, Bodhi says he never quite got caught up in the “scenes of the counterculture.”

“I enjoyed my time there [at BC], but it’s sort of in the mist of memory,” he said. He does remember most of the buildings, specifically remembering a classics class he took in Whitehead, (a building that as far as I know no longer holds any classics classes).

And he does remember his trips to the now-defunct campus bookstore in Boylan, where he happened upon what would become the path for the rest of his life.

While browsing the shelves he discovered books on Buddhism. “They aroused my curiosity,” he said. “The Buddhist teachings seemed to me to give a clear analysis and diagnosis of the human condition […] and it provided practical methods of self training. It encouraged investigation.”

From there, his interest in Buddhism only grew as he continued at Brooklyn up until his graduation with the class of 1966. It was in graduate school, at Claremont Graduate University outside of Los Angeles, that his Buddhist studies became a major factor in his life.

During his second semester of grad school, where he was working towards an eventual PhD in Philosophy, a Buddhist monk came to study there, and moved into the same residence hall as Bodhi.

“I thought this was an opportunity to learn Buddhism firsthand,” he said. He specifically wanted to gain more knowledge and practical teachings in the art of meditation, a large part of most Buddhist practice that he struggled with in the early days of his learning. “I thought it was just a matter of sitting down and focusing the mind, and the mind would immediately go into some kind of deep state of mediative absolution,” he said, laughing at his naivete at the time. Of course, now, he leads others in the same practices all over the world.

In early 1967, Bodhi began regularly meeting with and learning from his new teacher, a Vietnamese man named Thich Gic Duc. Eventually he moved in with the monk, first on-campus and then off.

“Through my association with him I realized I wanted to become a Buddhist monk myself,” Bodhi said.

In May of 1967, he received a novice ordination into the Vietnamese Buddhist order. Bodhi says that despite the step from a seemingly average life as Brooklyn-born Jew to that of a Buddhist Monk, a moniker which comes with a strict set of lifestyle guidelines, there was very little trouble in coming to the decision.

“People on the outside tell me it seems like such a drastic decision,” Bodhi said. “It felt like the natural fulfillment of that urge to live a deep spiritual life. […] There was no struggle, no period of indecision.”

Of course, after you’re ordained, the work in learning only intensifies. Not only was he learning the ins and outs of a monastic life, he was also going to school, teaching a class on world religions at Cal State in Fullerton while working on his dissertation.

Between 1971 and 1972, while living at a mediation center in Los Angeles, Bodhi was introduced to a group of passing monks from the small island of Sri Lanka, just south of India’s tip. Sri Lankan Buddhism, known as Theravada Buddhism, is slightly different than the Vietnamese Mahayana form that Bodhi had been studying (although both are based in core Buddhist teachings).

In 1972, Bodhi decided to take his Buddhist learning to Sri Lanka to take ordination there under in Theravada tradition at the age of 28.

“In the early days it was quite difficult,” he said of his new life on a monastery in Sri Lanka. “It was difficult to adapt to the different culture, and a very simple way of living.”

The monastery had no electricity, no running water, and the one-room cottage (known as a kuti) he lived in had walls made of mud, straw, and cow dung. He eventually got more or less used to it, and stayed at the monastery for three-and-a-half years before continuing his journey to India at the invitation of another monk. There, he made the Buddhist pilgrimage and taught classes to other monks.

After nine months in India, Bodhi returned stateside. He moved to a monastery in Washington D.C. called the Washington Buddhist Vihara, the very first Theravada Buddhist monastic community in America. He spent five years there from 1977 to 1982 before returning to Sri Lanka after a planned trip to the nation of Burma (now Myanmar) was derailed due to the political climate there. This stay in the island nation lasted quite a bit longer than the last one, spending almost all of the next two decades there, from 1982 to 2002.

In 1984 he became the English language editor of a Buddhist publication called the Buddhist Publication Society, a quarterly outlet that spreads Buddhist literature around the globe. He worked in that capacity until 1988 before taking over as its President until 2010.

Bodhi’s life in the Buddhist teachings have brought him to pastures all around the world, and even some more notable ones closer to home. In 1999 the United Nations made Vesak (a major holiday in the Buddhist faith which celebrates the birth, death, and enlightenment of the historical Buddha) an international holiday. In 2000, they held their first official celebration of the holiday, with Bhikkhu Bodhi as its keynote speaker.

“The first time I was really nervous,” he said. “I saw the UN in the distance and I got nervous, but I felt relieved that I had typed up the text.” He has addressed the UN several times since then, including earlier this year, where he addressed concerns with climate change. Now, he says, he “has no fear at all,” and only works off notes.

In 2007, he wrote an essay to a Buddhist publication criticizing the way most Americans adopted Buddhist teachings. He questioned how most in the West adopted Buddhism as an inward endeavor for personal growth, but very rarely projected the teachings outward to better the world around them. “We pursue them largely as inward subjective experiences geared toward personal transformation. Too seldom does this type of compassion roll up its sleeves and step into the field,” he wrote.

In 2008, he and a few other monks got together and began to put his ideas into practice. What came out of those discussions was Buddhist Global Relief, an organization with the aim of pushing charitable causes around the world. BGR embarks on “about 35 to 40 projects per year,” spanning from making donations after natural disasters (such as the earthquake in Nepal in 2015) to pushing for women’s rights.

Bodhi currently resides at Chuang Yen and sits as President of the Buddhist Association of the United States. From day to day, he continues to teach classes and spread the teachings that has helped guide him throughout the majority of his adult life. Of course, his own learning will always continue as grows and expands his own understanding of the world. These days?

“I spend quite a lot of time reading Chinese.”