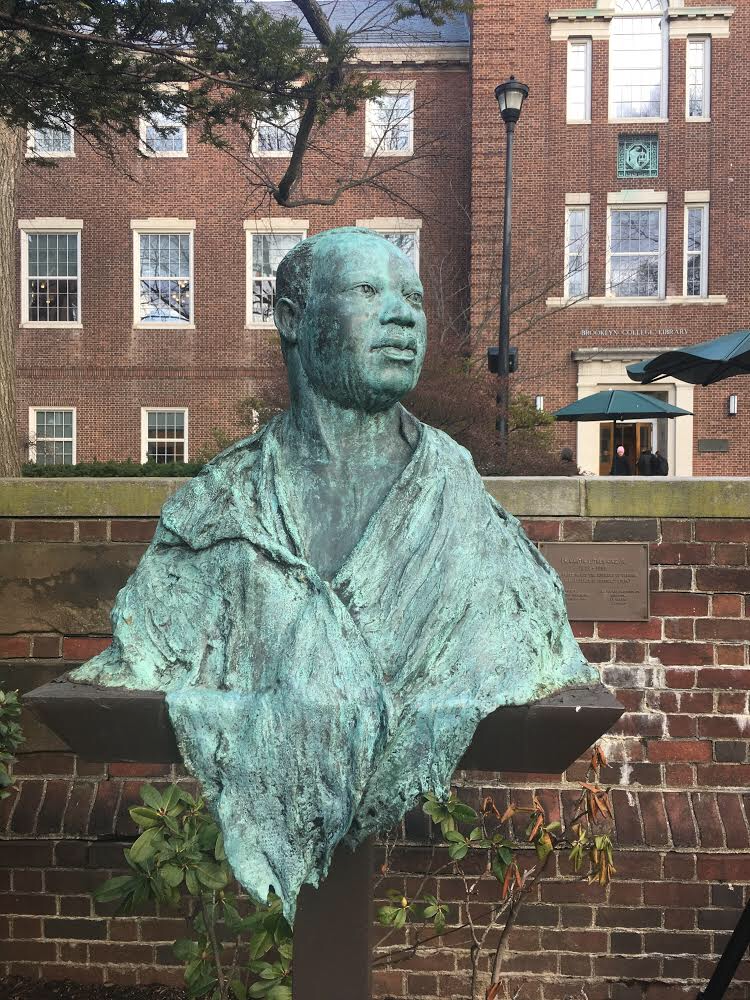

His chin is up, head cocked to the left. Draped over his relaxed shoulders, the tattered cloth extends down and hangs over the solid base of the bronze bust. The weathered garb bears the mark of the artist’s hand; as you walk around it, the visible indents of eager thumbs become apparent. Careful, imperfect, expressive and painterly. The year it was sculpted is engraved on the back of his shoulder, sloping downwards next to the signature of the artist. The bust’s cloth detail harkens back to slavery, and evokes the pain and pride which the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. has come to represent. Cast entirely in bronze, the rendering carries the likeness of the black cultural and political leader, but pushes against a rigid historicity – the work itself folds layers of meaning onto the figure himself, as well as into American history. Standing at the foot of the stairs leading to the library and triumphantly overlooking the east quad towards Ingersoll Hall, it’s but one example of the late Henderson Day “Bo” Walker’s public monuments.

Bo had done sculptures and drawings of many black leaders, including Malcolm X and Marcus Garvey. Countless numbers of these works have fallen into the hands of private collectors, but the bust of Dr. King remains on campus.

“I remember being at the unveiling of the Martin Luther King bust. He was so honored and I was so proud of him that day. I was 10, and he passed when I was 11. It was really timely, really momentous. And there was the award, too. He had gotten that recognition right before he left this earth,” said Bo’s daughter, Panya Walker, as she remembers that day in 1985, when the sculpture was gifted to the College. There, Bo was also awarded the Presidential Medal in honor of his work for the black cultural community.

Bo’s legacy of love for sculpture and for black cultural leaders is permanently imprinted onto the Brooklyn College campus. His story, and that of his family’s, reaches past the five boroughs and extends far back into history, at one point crossing paths with the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. himself.

As for many black Americans, the story begins in the segregated south.

Bo Walker was never extensively written about; most of what is known about the artist’s life and work is passed down orally from his family and friends. His brother, Frank Walker, who lives and works as an artist in the family’s native Charlottesville, Virginia, has many stories to tell first-hand.

The brothers were born in the basement of a local Charlottesville hospital, then the labor and delivery unit for black folk; Bo in 1951 and Frank in 1953. They had been drawing since their days in elementary school – sketching figures in their school workbooks, mimicking cartoons and comic book characters.

In the summer of 1967, Frank and Bo, as well as their two friends, Gerald E. “Gerry” Mitchell and Earl Gordon, showcased their art in the backyard of Mitchell’s home. That day, the boys made a collective $25 selling their drawings, which were pinned to clotheslines and strewn about the yard.

“That was way back when a hamburger cost five or ten cents, $25 was a lot of money then. You’re talkin’ many moon pies and hamburgers down the road. Could’ve got diabetes from that one show!” Frank laughed, but the soliloquy soon turned somber. “and that was the start of it all, the four of us would all become artists. Now I’m the only one left,” said Frank solemnly, as he recounted his bittersweet formative years in the rancorous pre-integrated south.

In their adult lives, Gerry and Earl became art teachers, inspiring and passing on the torch to their community’s youth for many years after that pivotal backyard show. In 2012, at the Jefferson School African American Heritage Center, a show entitled “From Backyard Clotheslines to Museum Walls,” curated by Andrea Douglas, paid homage to that very day and included recent works from Frank and Gerry. Gerry died just a few months before the show in 2011, and Earl in 2016.

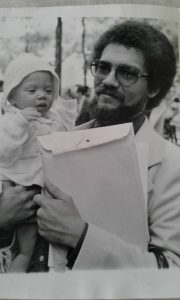

Pratt, holding his infant daughter.

When it was time for the brothers to go off to college, Frank chose the Army, where he would eventually become a draftsman and Bo chose to go off to Stanford.

Though first exposed to sculpture at Stanford, Bo’s passion for sculpture, which would come to define the rest of his artistic life, came to fruition at Pratt. A puppeteer friend of his at Pratt came to Bo with the task of designing and sculpting the heads for his puppets, Bo accepted. That, according to Panya, may have been the paradigm shift in his artistic career which led the artist to pursue sculpture.

After his brief stint at Stanford University, Bo ended up at the Pratt Institute, where he met Panya’s mother, Jocelyn. In 1974, the year before Bo would graduate with honors, Panya was born.

“My mother always told me stories of my father going around the Pratt campus with me bundled in his arms,” said Panya, beaming through the phone as she reminisced about growing up in Fort Greene, Brooklyn. “When people would inquire about what he was holding, he would say: ‘this is my greatest masterpiece!’”

A few flights up an old freight elevator would lead to the spacious studio that Bo obtained after having graduated from Pratt, close to campus and not far from his family’s home. That studio was the site of creation for many of his most famous works, including the bust of Dr. Martin Luther King, but it was also home to Panya’s fondest memories of her father.

“With whatever he was working on, he would sit me down next to him and start working, and I would work too. As a parent, he was always present, he brought me into his world: He wouldn’t just show me what he was doing, he would let me do it, too–let me get my hands dirty,” recalled Panya, choking back tears as she tells of her transformative childhood visits to her father’s studio.

Frank had similar stories about the studio, which he would always visit on his trips to New York from Virginia. For the brothers, their shared passion for art making was at the crux of their bond. And though they lived over 300 miles apart, they shared countless conversations over the phone, talking through their processes and bouncing ideas off of each other.

Growing up in the segregated south, the rich history of black folk was largely excluded from his education; instead, he was endlessly inspired by his own research into his people’s stories.

“Black history was hidden for so many years. We learned white history,” Frank said. “You explored your people’s history on your own, you gathered that material on your own. Or else you wouldn’t know anything about yourself.”

Bo and Frank never really knew their father, Henderson Day Walker. Both Panya and Frank insist that that’s why Bo looked up so fervently to strong black male role models – he constantly sought to elevate leading black figures as integral to American history. The Walker brothers’ mother, Marion Teresa Jackson Walker Price, who is now 94 years old and under Frank’s care, was an educator and typist in her younger years before becoming a librarian. She comes from a long line of innovators, educators, community organizers and businessmen, all of whom were the subject of Bo’s childhood stories.

In the late 19th century, Bo’s great-great uncle, Rinaldo Cox, began working as a stage manager and advertiser for a theater company in Charlottesville. (Among his clientele was Al Jolson, the infamous blackface performer.) Rinaldo passed the torch onto W.E. Jackson (Bo’s grandfather), who took the company even further, eventually subcontracting the business to an ad company in Richmond. The company came to be known as Jackson Poster Advertising, and a mainstay in the advertising world of Charlottesville. In the 1960’s, when blacks were finally able to acquire business licenses in Virginia, Jackson Poster Advertising expanded to an outdoor advertising franchise, meaning that anybody who wanted to advertise their business in Charlottesville, black or white, had to go through this black-owned company.

In the late 1950’s, Bo’s uncle Edward Jackson opened up the Bren-Wana. One of the first integrated restaurants in Charlottesville, the Bren was also a nightclub, a hotel, and a safe haven for black travellers who were not allowed to stay at commercial lodgings for white people. Situated on a hillside overlooking the Blue Ridge Mountains, the Bren played host to many jazz and blues musicians, including Duke Ellington’s band.

It was here that the Walkers’ path intersected with the King. In March of 1963, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. came to Charlottesville to give a talk at the University of Virginia. The event, organized in part by the historian and activist Paul Gaston (also a professor of Panya’s when she attended UVA), required King to stay overnight at the Gallery Court Motel. After the talk, with limited options for places to dine, King and his integrated group of activists and scholars stayed at the Bren-Wana.

With these strong black figures influencing his life and artistry, Bo Walker got to work, capturing their likenesses with a distinct reverence and idiosyncratic liveliness. At the Law School Library at Columbia University, there’s a bronze bust of Paul Robeson. And, on a smaller scale, in the collection of the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, up in Harlem, is Bo’s Frederick Douglas Ikenga, an eccentric iron and wood sculpture that’s a favorite of both Panya and Frank.

Bo’s artistry extended to many different mediums as well, he was an avid photographer, did countless drawings in pen and ink, and worked as a restorer and historian of African art.

In 1986, within a year of the unveiling of the bust of Dr. King, Bo Walker passed away from pneumonia at the age of 35.

In the days after Bo’s death, Frank went up to New York one last time, to clean out his brother’s workplace. Before stepping into the studio, Frank had remained stoic in the face of his brother’s passing, but the loft’s large windows flooded the space light, and the smell of clay, wax, and paint was still fecund, lush in the air.

“Like a child,” he said, “I wept and howled for the first and only time in my adult life.”

Thirty-five years later, Bo’s sculpture of Dr. King still stands on campus, seafoam green from oxidation, and nearly as old as its creator was. That sculpture also stands as a testament to the raw skill, craftsmanship, and spirit of its artist. For Panya and Frank, the sculpture represents their family’s legacy of black resilience, entrepreneurship, and creativity– a tribute to the legacy of not one, but two great men.