Over the summer and into the fall, we have all been subjected to the recurring battle cries whose message revolves around the necessity to vote. I choose the word “subjected” carefully on account of a lot of the language we are seeing are rings of the privilege we are afforded or the responsibility we have to cast our ballot this November. An unfortunate consequence of this language is that it sets an expectation that is easy for people to feel. It seems to insist that failing to meet those expectations is an act of falling short or letting other people down. I think the expectations that are set for people to put their head down and vote is a sign of an unhealthy democracy. Dissent, confusion, and anger should be encouraged and platformed, not brushed under the rug until the coast is clear.

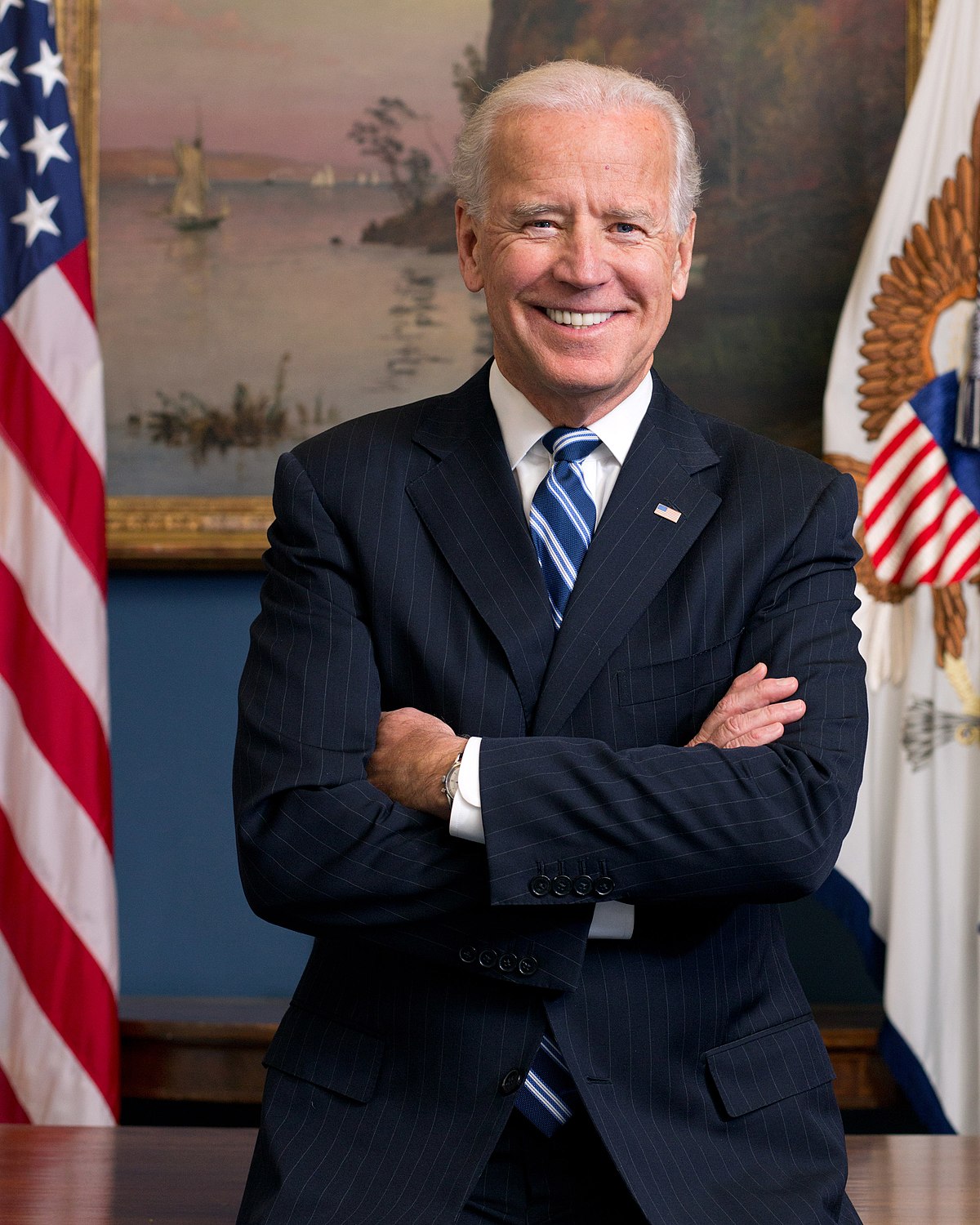

My thinking on the subject isn’t over the question of filling out a ballot, but more about the way we talk about voting. If one cares about trans rights, immigration, climate change, and choosing a progressive judge for the supreme court, the choice is obvious and doesn’t merit too much more thought as far as I am concerned. Biden is obviously the lesser of two evils, just as Hillary was in 2016, and just as Obama was in 2008 and 2012. These progressive politicians all have traits, platform planks, opinions, and personal beliefs that are at odds with a more just society. Obama and Hillary, for example — if we are to expand our concern outside of our own borders — have foreign policy records that would be laughable if it were not for the countless innocent deaths that resulted from them.

The problem then is that every four years, liberal voters are positioned in a drama where their vote is the only thing that stands between a budding facist regime. We are so easily seduced, and for good reason, by this life or death narrative that we lose sight of a reality where we can elect politicians who embody the same anger and pain as we do. For a number of issues, which I’ve mentioned, this election can be a matter of life and death. But the candidate that is positioned to represent us in those struggles doesn’t, and shouldn’t have to be a man that would be much more at peace in a retirement community.

But alas, we lowly citizens continually have to listen to popular artists, both contributors and curators of culture, not to mention politicians, tell us that our vote counts. It does, but they often leave out the important part: that we can use it to choose someone that we don’t feel like we have to settle for.

One such writer who doesn’t have much sympathy for those who aren’t excited to vote is David Sedaris, who took to The New Yorker to share his piece on undecided or uncertain voters. He wrote:

“To put them in perspective, I think of being on an airplane. The flight attendant comes down the aisle with her food cart and, eventually, parks it beside my seat. “Can I interest you in the chicken?” she asks. “Or would you prefer the platter of shit with bits of broken glass in it?”

To be undecided in this election is to pause for a moment and then ask how the chicken is cooked.”

My huge issue with this argument is the scenario in which it is framed. As the reader, we are presented with a reality that is straightforward: we are in a confined space and are offered two choices for something to eat. This framing does a good job skirting the issue that there are plenty of warranted grievances for not wanting either options. I, for one, am not a huge fan of chicken. And in lieu of having any other choice, as Sedaris sets the problem, then I am the fool for asking how the chicken is cooked.

This framing is a large part of the problem I have with the current political arena. People have real grievances. There are people living near the coasts who live in fear of the extreme weather which is a product of the changing climate. We see people being arrested in the streets for protesting police brutality, which is an institution that is both commonplace and vigorously preserved by lawmakers. And there are also people like myself, who, while being born a white male with all of the necessary privileges in order to realize a semblance of upward mobility, haven’t had access to dental insurance all their life.

There are truly endless grievances that shape the material reality of peoples’ lives both in the United States and in countries whose fate is tethered to our own. When these grievances aren’t embodied by a candidate, we should not have to be expected to put our head down and vote for them. We should be free and encouraged to criticize their records and demand that they cast their influence on issues that we all experience the impact of.

The nature of progressive politics is embedded in the understanding that change is a process and that real progress isn’t achieved within a day’s work, let alone a presidential term. Joe Biden is at the end of a movement that has serious demands. His record and his current posturing simply does not embody the anger and frustration that most Americans feel. While I won’t be withholding my vote from Biden, I will continue to be a harsh critic of him and actively resist attempts to frame the choice between him and Trump as the only thing we could have done.

If we are to sit down with regular Americans who aren’t crazy about the idea of voting, in most cases it is not for a lack of caring. The people of this country are intimately familiar with pain and the feeling of getting the raw end of the deal. Instead of telling them that the only way out of their plight is to vote for Joe, we should listen to what their problems are and put real pressure, not just posting on Instagram, on the politicians who most directly determine the form of our country.

To humor Sedaris one last time: if we are presented with only one palatable option, we should be asking ourselves “how did we get here?” What kind of airline could even offer a plate of defecation garnished with broken glass? Whichever kind, I think it would be well warranted to ask how the other dish is cooked. Bearing our well deserved skepticism, we can then talk to our neighbors about what a better menu could look like. Then maybe, once we’ve drafted a more inclusive program, we can start asking the real questions like “where are we going?”