In a time when theater is non-existent and concerts are rare, art lives on only in public where it is constantly surrounding us, especially in New York City. From statues of historic figures to spray-painted graffiti on walls, public art has engulfed our communities, but not always in the way that we think.

“Public art can include interventions, actions, research, and community-building as well.”

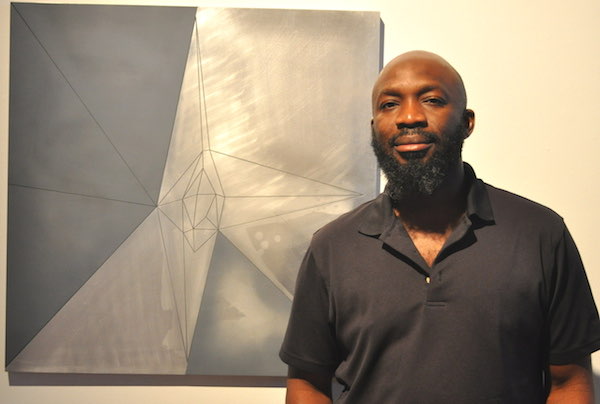

These are the words of Eto Otitigbe, an art professor at Brooklyn College who has specialized in different forms of public art frequently throughout his career. Otitigbe sat down to discuss these experiences with numerous art students and professors on Sept. 30, when the Department of Africana Studies invited him to speak at “Voices for Change,” an ongoing series that focuses on how people address certain issues through specific mediums.

Professor. Dale Byam, who hosted the event, introduced Otitigbe, saying his work is typically based on “the intersections of race, power, and technology with history as the foundation for exploration.”

In his work, Otitigbe attempts to set “alternative narratives into motion,” especially when it comes to a piece he worked on called Becoming Visible.

Becoming Visible is a series of carved images made of recycled plastic that depict a hooded Otitigbe and was a direct response to the acquittal of George Zimmerman, the man who killed Trayvon Martin, an unarmed black teenager in 2012.

“Trayvon Martin was wearing a hoodie when he was murdered, and I noticed on social media a lot of people…donned a hoodie as a symbol of protest,” Otitigbe explained. “So I too joined that action…and put on a hoodie myself.”

Otitigbe’s goal in doing so was to reappropriate the hoodie as a symbol from something negative to something that is “positive and powerful.”

“It has been really pivotal in my career as an artist,” Otitigbe revealed. “It has kind of catapulted me into another space.”

After his work on Becoming Visible, Otitigbe was invited to collaborate on a project at the University of Virginia that aimed to create a memorial dedicated to the enslaved laborers who contributed to the university’s upbringing and maintenance. Otitigbe joined the project after people from the university and Charlottesville made a specific request regarding the memorial.

“One bit of feedback they wanted was that the memorial needed to display a visual presence of those who were enslaved,” Otitigbe said.

This proved to be challenging, however, as the project’s team had over 4000 records of people who were enslaved with 900 names and only five photographs available. Of those five images, the team decided to use Isabella Gibbons, a woman who was enslaved at the University of Virginia.

“We decided to select Isabella Gibbons as someone who really exemplified that idea of triumph, hope or despair,” Otitigbe explained. “She went on to be an educator and opened the Jefferson school which is still in operation today as a community center.”

In designing this monument, the stone blocks acquired for the exterior posed a challenge to Otitigbe and the rest of the team, particularly the linear carving marks that remained from when they were excavated from the quarry. Ultimately, the team decided to keep them as representative of the enslaved people.

“These quarry marks are indicators of the kind of work that enslaved people would do,” Otitigbe explained. “Many of them did masonry-style work.”

While Otitigbe holds these projects in high regard, he made sure to clarify that his work transcends beyond subjects based on racial injustice. Otitigbe explained his interest in public art as an opportunity to explore his own curiosities and see where they take him.

“I think there is something seductive about finding a little piece of string in a sweater, pulling on it and having it take you on this adventure,” said Otitigbe. “For me that adventure involves a lot of research…and inserting myself in different communities and getting to know more about myself and more about the world.”

During his presentation, Otitigbe showed an image of himself at Jacob Riis Park in Rockaway Beach climbing a blue “puzzle piece” that was representative of a staircase into what he referred to as “an imaginary or alternative realm.” While simple in execution, Otitigbe thinks the image bears significant meaning.

“I think in a lot of ways it captures that idea of the exploration of curiosity and where it may lead,” Otitigbe shared. “I thought about public art as a way of working through, around, and with the different constraints and institutions that are involved in art-making and art consumption.”

While art can certainly be used to convey specific messages, Otitigbe expressed public art as a medium for the sake of “play.”

This includes one of Otitigbe’s first public artworks called Looping Back, a three-dimensional structure that was located on Randall’s Island for six months in 2013 and is made of tree bark from North Carolina.

“I really wanted to create artworks that were social in nature, that invited people to interact with them, that allowed people to claim these spaces and these artworks as something for themselves,” Otitigbe explained.

Throughout its tenure, Otitigbe would visit the park on occasion to check on his work. He often noticed children playing on it, as well as the structure being used as a BBQ pit. Such actions damaged the tree bark panels and required Otitigbe to frequently replace them.

“I was okay with that,” Otitigbe revealed. “I was really interested in what happens when you put something that is…really different in the space where it was situated.”

In the coming weeks, Otitigbe is scheduled to create a sculpture in Mount Vernon, New York, of the late Heavy D, a rapper known for the song “Peaceful Journey,” which the sculpture will be named after. As a hip-hop fan who grew up in Albany, Otitigbe was able to insert himself into the project.

“He was really an outstanding artist,” Otitigbe shared. “He had really positive lyrics, and his messages were really empowering.”

For Otitigbe, public art can take on many different forms. Whether it’s to draw attention to societal issues, have some fun, or commemorate a specific person, public art speaks to us in different ways.

“I think that issues related to human rights, racial justice, and also the environment are all really important things that I like to focus on in my work,” Otitigbe said. “I encourage all of you to go out and look at art and see art and think about how it transforms you.”