Marcus Reeves is an adjunct professor at NYU, but his knowledge doesn’t come from textbooks and long nights at the library. It comes from the hip-hop music of yesterday and today.

Reeves, who currently teaches a course in the history of hip-hop, is no stranger to the music scene, having worked as a content producer for VH1 and BET, as well as the deputy music editor at The Source magazine.

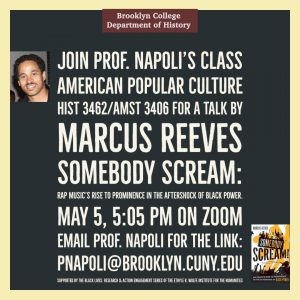

As a part the Black Lives Series from the Ethyle R. Wolfe Institute for the Humanities, Reeves joined History Professor Philip Napoli’s American Popular Culture class on May 5 to discuss his book “Somebody Scream!: Rap Music’s Rise to Prominence in the Aftershock of Black Power.”

Right off the bat, Reeves made it clear that he wanted to hear from the students present in the Zoom call.

“While I do know…a lot about hip-hop, [in] today’s landscape there are so many artists that I won’t know by name so I’m going to talk about hip-hop in terms of movements and concepts,” said Reeves. “What are some…of the hip-hop artists you like, and why do you like them?”

With answers like J. Cole and Kendrick Lamar to Drake and Jay-Z, the students set the rest of the discussion in motion as Reeves dove into the modernity of hip-hop and rap music. From Reeves’ perspective, hip-hop has entered a new phase within the last 10 years, a phase he calls “Hip-Hop Americana.”

“It’s basically this new phase where [hip-hop] already emerged, it’s already knocked at the door of the mainstream, it’s already walked into the mainstream, and created a new world,” said Reeves. “Now it’s pretty much an established part of the center of American mainstream culture.”

According to Reeves, this includes President Obama using hip-hop terms, Beyonce singing at the inauguration, the rise of Club Quarantine during the pandemic, and the late Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg being penned as “Notorious RBG,” a nickname inspired by The Notorious B.I.G, a bonafide rap legend born and raised right here in Brooklyn.

“No one had to ask ‘what were they referring to?” said Reeves. “Everyone knew what you’re talking about, and to be able to put a Supreme Court justice in the context of a hip-hop icon is…a pinch yourself moment.”

With that, Reeves made it a point to mention that hip-hop is the number one selling genre in the country and the most popular genre in American culture, which he referred to as “a big surprise” considering hip-hop had begun to die in popularity at one point.

In the early 2000s, as rap music got increasingly political and audiences got bored with the content, hip-hop found itself at a crossroads, and it was the internet that would change the genre as we know it.

“The internet changed the rules of hip-hop [and] how an artist was supposed to come out,” said Reeves. “Before the internet, a hip-hop artist had to make their bones through live shows, through battles, through working their way through a team of people, appearing on people’s records and there was a whole system set up by gatekeepers to kind of work on quality control.”

With the internet, artists were essentially able to bypass these traditional obstacles and immediately connect with audiences all over the world without having to rely on a label. Not to mention, the shift put attention on key artists who were white.

“In ‘Somebody Scream,’ I talk about how hip-hop became the voice not just of young Black people but of American youth,” said Reeves. “An artist doesn’t have to pay attention to what you feel about the culture because they can reach out immediately to an audience and just get those listens and…overlook the history of hip-hop.”

While this could be seen as problematic, Reeves noted that hip-hop is not necessarily something that is identified by race, gender or any identifying feature. Reeves specifically mentioned how Eminem and even country artists have used their music to discuss things that American popular music had not addressed.

“To have someone who’s white come into hip-hop with ‘skills’ and [be] able to talk about living in a trailer, growing up poor, that shows the world another side of America that America doesn’t allow to be seen in mass,” said Reeves.

In this way, the internet has been especially useful in spreading hip-hop and music to all parts of the world, but Reeves noted that the internet has been somewhat damaging to movements like Black Lives Matter or LGBTQ rights.

“I think the internet…diminished its power because now you don’t have to go to hip-hop to figure out what’s going on in the streets…you can just go to YouTube,” said Reeves. “White America knows more about Black oppression now through videos than they do through an NWA record.”

Regardless, Reeves remains consistent in the belief that hip-hop is a genre that is open to everyone and all kinds of stories.

“In hip-hop, there is room for everyone’s voice,” said Reeves. “It’s about standing where you are and telling your story and affirming who you are.”