On Thursday, Oct. 10, Brooklyn College’s biology department gathered in the library auditorium to memorialize their late chair, Dan Eshel.

Eshel taught at BC for 22 years before his death in November of 2015. According to his successor, Peter Lipke, the Department of Biology was so “devastated” by Eshel’s untimely passing that it took nearly four years to properly memorialize him. But memorialize him they did, both with a moving ceremony in the library auditorium, and with a permanent monument to Eshel and his wife: a pair of trees, planted on the East Quad.

Lipke and Eshel met in 2006, when Lipke transferred to Brooklyn after decades teaching at Hunter. The two had an instant connection – they had both been studying yeast – but soon they began to connect on a deeper, more personal level.

“I came to know him as a low-key colleague, notable for his complete indifference to self-promotion,” Lipke reminisced during the memorial.

Despite his modesty, his life story was quite impressive. Born in Israel in 1953, Eshel was 20 at the dawn of the 1973 Yom Kippur War. At one point he volunteered to walk through a field of bullets, sustaining gruesome injuries. As he recuperated, he watched his fellow soldiers die, including his best friend. But rather than let tragedy define his life, he devoted himself to science – and to his beloved wife, Ilana.

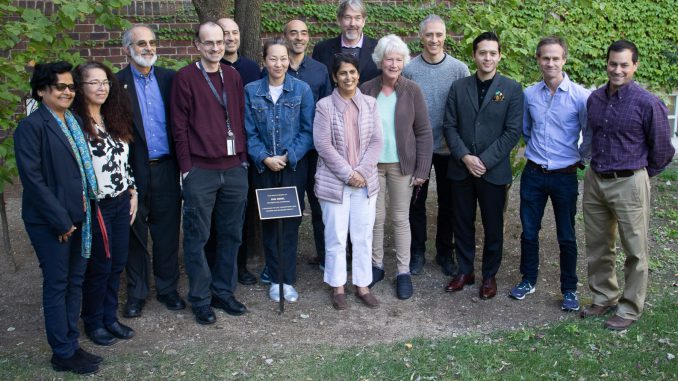

Eshel came to Brooklyn College in 1993, and touched the lives of every student and colleague he met. Over a dozen speakers came to his memorial that Thursday to share stories of their time with him.

Deputy chair Theodore Muth recalled coming to Brooklyn College in August of 2000 to find his lab missing basic supplies, when Eshel intervened.

“Dan cleared a bunch of space in his lab and invited me down, where I had access to centrifuges and freezers,” said Muth. “It’s not an exaggeration to say that in my first semester, I spent more time in Dan’s lab than my own.” Muth found himself turning to Eshel all throughout his career – first when navigating the tenure process, and then to help his Israeli-born wife acclimate to America. Sometimes, Eshel would invite Muth to his apartment complex in Hoboken, just to spy on his neighbor Eli Manning in the gym.

But the most touching tribute came from Eshel’s longtime friend, professor emeritus Ray Gavin. Gavin was there in 1993 when Eshel first came to campus, and in his memory, ‘93 was an “exciting year.” It was the year campus-wide e-mail had finally come to BC; and it was the year the biology department received a million-dollar grant from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute to hire a molecular biologist onto the faculty. The department interviewed five people for the open position, but Eshel was far and away the favorite. Gavin interviewed Dan and Ilana Eshel over a meal at a Manhattan restaurant – the first of many in a friendship that would last two decades.

“We listened to Mozart, gazed at the skyline, and ate lentils – every vegan’s favorite!” Gavin remarked. One night, over dinner, Gavin commissioned a life-size portrait of himself from Ilana.

“I’m still waiting!” he joked.

“Dan Eshel died in the midst of his usefulness,” Gavin said. “Although he did not finish the course, he always kept the faith.”

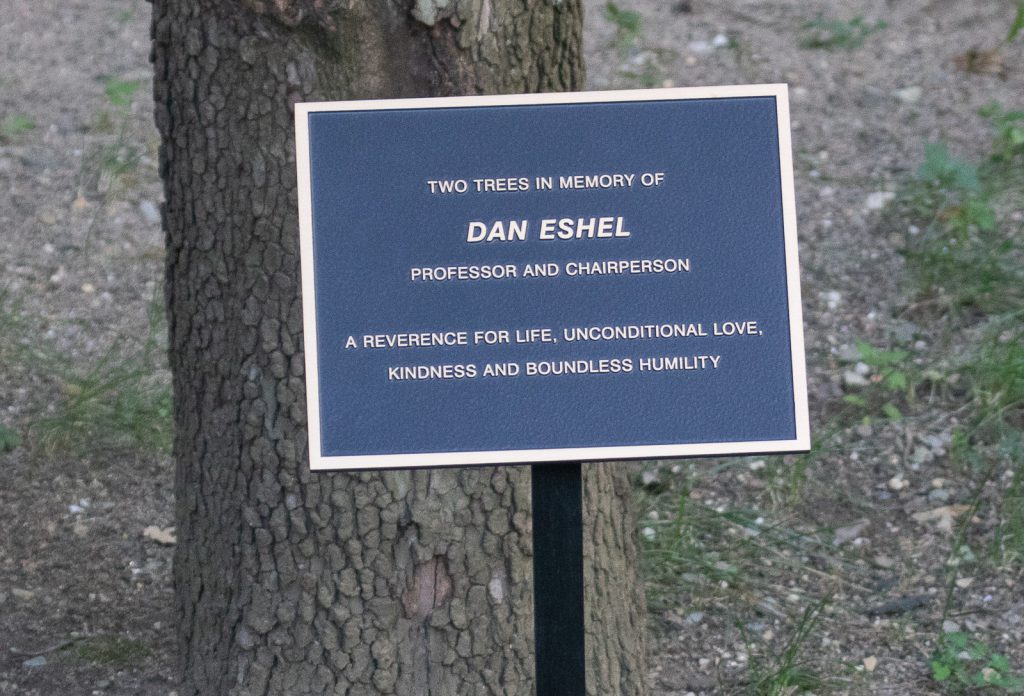

While the ceremony made it clear that Eshel had left his mark on the campus, that mark on the campus was literal as well. After the memorial, the crowd congregated in front of New Ingersoll, where Gavin and Ilana Eshel unveiled a plaque in Dan Eshel’s honor. To its left and right, the campus planted seeds which will eventually sprout into a pair of trees – one salt cedar, and one oak.

The choice of trees is a symbolic one, meant to represent Eshel and his beloved wife.

“The book of Genesis informs us that the prophet Abraham planted an Eshel tree in Beersheba,” Gavin explained. “Eshel” comes from the Hebrew word for a tamarisk tree or salt cedar; the name “Ilana” derives from the Hebrew for “oak tree.”

“Dan was the deep-rooted, tolerant tamarisk,” said Gavin, “and Ilana the long-living and majestic oak.”

It was an understated and heartfelt tribute to an understated man. But perhaps the most heartwarming tribute to Eshel came when he was still alive. He had just delivered his final lecture of the semester, in what would be the final lecture he ever taught. As he wrapped up his lesson, he looked up to see his entire class on their feet – not to leave, but to give him a standing ovation.